Introduction

The majority of films produced in Cyprus after the Greek junta-led coup and subsequent Turkish military offensive of 1974, whether their origins are Greek-Cypriot or Turkish-Cypriot, can be considered examples of the “cinemas of the Cyprus Problem” and “the excess of the political.” [1] In what is perhaps the first published critical evaluation of the development of Cypriot cinema before the establishment of the Cinema Advisory Committee in 1994, Soula Kleanthous-Hadjikyriakou offers a rather daring (considering the dominant politics of the period in which she was writing) critical position on the Greek-Cypriot films produced between 1974 and 1986 – the year that her account was first presented at a Cyprus Association for the Arts and Communication conference on Cypriot Cinema. Her evaluation is to a certain extent dismissive, applying the adjective “miserable” and concluding that in this period the Republic of Cyprus treated the cinema as either a medium of propaganda or as part of a campaign to stimulate tourism. [2]

This article will focus on four films that are neither explicitly political nor ‘miserable’, but instead constitute a ‘colourful’ example of popular, commercial cinema. Three of these films were co-produced in the early-1980s by movie theater owner turned producer Diogenis Herodotou and can be considered rip-offs of the Italian ‘Black Emanuelle’ series starring the Indonesian actress Laura Gemser which was initiated by Bitto Albertini’s Emanuelle nera/ Black Emanuelle (1975) – itself a rip-off of Just Jaeckin’s game-changing French production Emmanuelle (1974). The fourth film is Hasaboulia tis Kyprou [Hassanpoulia: The Avengers of Cyprus], directed by Kostas Dimitriou between 1974 and 1975, partially in Greece during the golden period of Greek soft-core and erotic cinema, and often associated with the tagline ‘the film that increased the birth rate in Cyprus.’

These films are often listed in the existing literature on the history of Cypriot cinema, but they have only recently been discussed in relation to the broader categories of erotic, soft-core or sexploitation films. [3] For example, a brief section in Shiafkalis’ collection of essays on the development of cinema in Cyprus focuses on Herodotou; [4] however, the author appears to be unaware of the titillating content of Herodotou’s international co-productions and simply celebrates his efforts to persuade foreign productions to use Cyprus as a filming location. More recently Ilias Milonakos’ I Mmavri Emmanouella/ Emanuelle: Queen of Sados/ Emanuelle: Queen Bitch (1980) has been listed as an example of Greek (as opposed to Cypriot) soft-core cinema and celebrated as one of the international triumphs of Greek erotic filmmaking. [5] Online synopses typically refer to the shooting location of the film as an unspecified Greek island and Gary Needham cites the film as a key case study of Greek films that ‘reflect the more statistically popular, most commonly purchased and most frequently viewed Greek films’ outside Greece. [6] Even though the film is directed by Ilias Mylonakos, one of the leading filmmakers of Greek erotic cinema, the contribution of co-producer Diogenis Herodotou, who has been hailed as a pioneer of the development of commercial filmmaking in Cyprus, [7] should not be overlooked. Given his involvement, which allowed the film to be shot on the island, Emanuelle: Queen of Sados should in fact be considered a Greek-Cypriot co-production (credits on prints of the film identify it as such, with the addition of some uncredited Italian financing from C.R.C. - Cinematografica Romana Cineproduzioni) and therefore a key example of the Cypriot soft-core cycle.

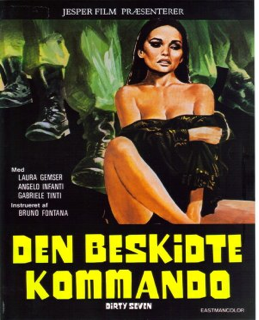

Herodotou initially established economically motivated collaborations with Greek production companies and later devoted his efforts towards establishing Cyprus as a filming location for international co-productions such as the Greek Ishyri Ddosi... Ssex [Strong Dose… Sex]/ Operation Orient (1977), directed by Ilias Milonakos and starring Anna Maria Clementi, and the two films starring Laura Gemser that complete the Cypriot Black Emanuelle trilogy: the West German Die Todesgöttin des Liebescamps/ Love Cult/ Love Camp/ Divine Emanuelle: Love Cult (1981), directed by Christian Anders, and the Italian La belva dalla calda pelle / The Dirty Seven/ Emanuelle: Queen of the Desert (1980, but not released until 1983), directed by Bruno Fontana.

The majority of films produced in Cyprus after the Greek junta-led coup and subsequent Turkish military offensive of 1974, whether their origins are Greek-Cypriot or Turkish-Cypriot, can be considered examples of the “cinemas of the Cyprus Problem” and “the excess of the political.” [1] In what is perhaps the first published critical evaluation of the development of Cypriot cinema before the establishment of the Cinema Advisory Committee in 1994, Soula Kleanthous-Hadjikyriakou offers a rather daring (considering the dominant politics of the period in which she was writing) critical position on the Greek-Cypriot films produced between 1974 and 1986 – the year that her account was first presented at a Cyprus Association for the Arts and Communication conference on Cypriot Cinema. Her evaluation is to a certain extent dismissive, applying the adjective “miserable” and concluding that in this period the Republic of Cyprus treated the cinema as either a medium of propaganda or as part of a campaign to stimulate tourism. [2]

This article will focus on four films that are neither explicitly political nor ‘miserable’, but instead constitute a ‘colourful’ example of popular, commercial cinema. Three of these films were co-produced in the early-1980s by movie theater owner turned producer Diogenis Herodotou and can be considered rip-offs of the Italian ‘Black Emanuelle’ series starring the Indonesian actress Laura Gemser which was initiated by Bitto Albertini’s Emanuelle nera/ Black Emanuelle (1975) – itself a rip-off of Just Jaeckin’s game-changing French production Emmanuelle (1974). The fourth film is Hasaboulia tis Kyprou [Hassanpoulia: The Avengers of Cyprus], directed by Kostas Dimitriou between 1974 and 1975, partially in Greece during the golden period of Greek soft-core and erotic cinema, and often associated with the tagline ‘the film that increased the birth rate in Cyprus.’

These films are often listed in the existing literature on the history of Cypriot cinema, but they have only recently been discussed in relation to the broader categories of erotic, soft-core or sexploitation films. [3] For example, a brief section in Shiafkalis’ collection of essays on the development of cinema in Cyprus focuses on Herodotou; [4] however, the author appears to be unaware of the titillating content of Herodotou’s international co-productions and simply celebrates his efforts to persuade foreign productions to use Cyprus as a filming location. More recently Ilias Milonakos’ I Mmavri Emmanouella/ Emanuelle: Queen of Sados/ Emanuelle: Queen Bitch (1980) has been listed as an example of Greek (as opposed to Cypriot) soft-core cinema and celebrated as one of the international triumphs of Greek erotic filmmaking. [5] Online synopses typically refer to the shooting location of the film as an unspecified Greek island and Gary Needham cites the film as a key case study of Greek films that ‘reflect the more statistically popular, most commonly purchased and most frequently viewed Greek films’ outside Greece. [6] Even though the film is directed by Ilias Mylonakos, one of the leading filmmakers of Greek erotic cinema, the contribution of co-producer Diogenis Herodotou, who has been hailed as a pioneer of the development of commercial filmmaking in Cyprus, [7] should not be overlooked. Given his involvement, which allowed the film to be shot on the island, Emanuelle: Queen of Sados should in fact be considered a Greek-Cypriot co-production (credits on prints of the film identify it as such, with the addition of some uncredited Italian financing from C.R.C. - Cinematografica Romana Cineproduzioni) and therefore a key example of the Cypriot soft-core cycle.

Herodotou initially established economically motivated collaborations with Greek production companies and later devoted his efforts towards establishing Cyprus as a filming location for international co-productions such as the Greek Ishyri Ddosi... Ssex [Strong Dose… Sex]/ Operation Orient (1977), directed by Ilias Milonakos and starring Anna Maria Clementi, and the two films starring Laura Gemser that complete the Cypriot Black Emanuelle trilogy: the West German Die Todesgöttin des Liebescamps/ Love Cult/ Love Camp/ Divine Emanuelle: Love Cult (1981), directed by Christian Anders, and the Italian La belva dalla calda pelle / The Dirty Seven/ Emanuelle: Queen of the Desert (1980, but not released until 1983), directed by Bruno Fontana.

The following sections of this article offer an overview of the emergence of erotic filmmaking in Greece and explain the relationship between Greek and Greek-Cypriot cinema under the rubric of alternative affinitive transnationalism. The remainder of the article will then present a transgressive reading of the case study films, demonstrating how they form intertextual and extra-textual associations that disrupt dominant (re)presentations of Cypriot politics.

Strictly Inappropriate: The Context

According to Vrasidas Karalis, the principal antagonist of the New Greek Cinema of the 1970s was not the military dictatorship of the Greek colonels (a.k.a. Greek Junta; 1967-1974), but a group of films that operated under a system of production, distribution and exhibition that was implicitly tolerated by the political establishment; [8] these films were screened in suburban cinemas and labelled as “strictly inappropriate.” [9] Karalis notes that “in the most political year of 1975, Angelopoulos’ and Koundouros’ groundbreaking films were selling fewer tickets than the venerable Women Lusting for Sex, Honey on Her Body, My Body on Your Body and Her Lustful Body!” [10] He goes on to explain that one of the key factors that led to the dominance of the erotic films in as a popular form of cinematic entertainment in Greece – and which gradually spread to prestigious venues in the city of Athens – was the rising popularity of television and later the straight-to-video distribution of films, which became a standard practice during the 1980s. The video era produced a large number of slapstick comedies, sex comedies and pornographic films and constitutes a second period of ‘low-brow’ Greek ‘cinema’ (more recently re-categorised as cult cinema) which remains uncharted by scholarly criticism on Greek cinema in English. Gary Needham’s investigation of the distribution of Greek films released on video in the UK during the period 1979-1984 illustrates that “the dominant experience of Greek cinema by the majority of UK viewers in the 1980s was defined” by films such as Emanuelle: Queen of Sados, Vangelis Serdaris To Koritsi ke to Alogo/ Confessions of a Riding Mistress (1973) and Omiros Efstratiadis’ Pio Thermi ki ap’ ton Ilio/ The Lady Is a Whore (1972). [11]

Two recent publications, both written in Greek, focus on the emergence and development of erotic films and the VHS period in Greece. [12] According to Komninou and Kassaveti the number of cinema ticket sales in Greece declined by a total of 73 million from 1969 to 1973, [13] and the development of erotic cinema was an attempt to counter this downward trend. The authors add that Greek erotic cinema did not emerge out of nowhere as it borrows the sexual innuendos of the cinema of the previous decade, which they describe as ‘youth delinquency’ dramas dressed with the familiar conventions of crime-thrillers.[14] Thus, the erotic films of the early 1970s transformed these innuendos into elaborate, initially sensual, erotic numbers (the nude protagonists caress and kiss on a bed without even simulating sexual intercourse). Komninou and Kassaveti write that the success of this erotic cinema owes much to the producer Grigoris Dimitropoulos’ private interest in the financing of these films and his collaboration with filmmaker Omiros Efstratiadis, who together with Ilias Milonakos, was the leading director of this genre and later of softcore films that featured less restrained sexual scenes. Gary Needham notes that the “first features to be seen in the crystal clear clarity of DVD were not lovingly restored box sets of Finos comedies, but a series called ‘The Greek Erotica Collection”’, [15] which predominantly included films directed by Ilias Milonakos. Efstratiadis’ erotic films capitalised on the ‘three Ss’ (summer, sex and souvlaki) of the Greek tourist industry and “were made on Greek islands with international casts.” [16] Needham’s analysis of Milonakos’ films concludes that the latter’s authorial signature is the doubling of beautiful landscapes with the objectification of the female body as a “singular visual spectacle”, [17] a process non dissimilar from that of the French Emmanuelle series and the imitations it spawned.

The addition of ‘nastier’ words in the translated titles of Greek erotic films – or occasionally even in the Greek titles of such films, which were initially distributed as international co-productions – depended on the explicitness of the sexual scenes included in the various international versions. Both Komninou and Kassaveti and Karalis note that soft-core films were released in two versions: “one was for local consumption, without explicit sex, but with lots of titillation, and sometimes starring important mainstream actors. Another version, with explicit sex scenes, was made for markets like Denmark, Sweden, the United Kingdom, Turkey, Germany […] (Of course, most of them were reimported, sometimes dubbed in other languages).” [18] The above commentators add that cinema owners in Greece typically inserted non-diegetic hardcore footage utilising different actors in different locations into the screening of soft-core films. This practice became known as tsonta and, apart from entertaining the male moviegoers who verbally celebrated this practice while viewing the film, it was also seen as an underground response to the censorship system imposed by the Greek Junta.

By the mid-1970s Greek soft-core cinema reflected practices that may best be described as a form of alternative transnationalism, in which remnants of thriving European film industries (such as that of Italy) prior to the advent of TV and VHS formed exchanges that were driven by the cinematic language of explicit sex and violence, which was not limited to ‘low-brow’ cinema, but rather extended to arthouse existentialist psychosexual dramas. [19] According to Karalis, the explosion of soft-core pornography must be seen “within the wider context of sexual liberation […] Greek porn films belong to the golden age of the genre worldwide.” [20] Mathijs and Mendik use the word ‘alternative’ to describe the golden age of Eurotrash and exploitation cinema; [21] thus ‘Alternative European cinema’, as understood by the two authors, does not refer to ‘accepted’ forms of European arthouse cinema, but rather to an alternative history of European cinema that “sets itself not just against a mainstream culture, but also against a range of ways of thinking.” [22] Therefore, at a time when the dictatorship attempted to normalize social behavior according to the slogan ‘Greece of Greek Christians’, the making and consumption of erotic films carried an inherent act of resistance against the political power structure, religion and tradition. [23] The political or transgressive reading of these films by Greek scholars and film historians like Karalis [24] constitutes the starting point for this article’s analysis of the four case studies as alternative forms of a Greek-Cypriot cinema that set themselves against the dominant paradigm of the cinema of the Cyprus Problem.

The Cyprus Connection

The majority of Cypriot films are regional or supranational co-productions, and the country of production that most frequently appears next to Cyprus is Greece. Therefore, the principal co-production model that characterises Greek-Cypriot Cinema is what Mette Hjört terms ‘affinitive transnationalism’, which can be defined as the “collaboration across national borders with “people like us”, the perception of similarity being based in many cases on ethnicity, culture, and language, although commonality may center on core attitudes, interests, concerns and problems.” [25] This transnational collaboration predates the introduction of official film policy by the Republic of Cyprus in 1984. The first attempts (in the 1960s) to produce cinematic works in Cyprus were private initiatives and so the lack of infrastructure, the inexperience of the pioneers of Cypriot cinema and the commonalities (in terms of ethnicity, language, religion and culture) between the Greek-Cypriot community and Greece led to collaborations that helped drive the development of Cypriot Cinema, both before and after the establishment of the Cinema Advisory Committee in 1994.

Diogenis Herodotou’s entrepreneurial activity in the area of financing and producing films is an early example of affinitive transnationalism between the Greek film industry and a then-embryonic Cypriot cinema. Diakopes stin Kypro Mas [Vacation in Our Cyprus] (1971) is an early example of this collaboration; the film featured popular Greek actors as the main protagonists and was directed by Orestis Laskos, who also directed Dafnis kai Hloi/ Daphnis and Chloe (1931), a silent film which is “usually credited with the first nude scene in European cinema.” [26] According to Stylianou-Lambert and Philippou “no other film resembles a colorful promotional trailer for Cyprus more than Vacation in Our Cyprus.” [27] The authors go on to note that the main characters of the film “seem determined to visit every guidebook destination on the island” and that the Island of Cyprus is “portrayed as the happy birthplace of Aphrodite, the Goddess of beauty and love.” [28] Herodotou’s later Black Emanuelle films seem to revisit this postcard-style of filmmaking; however his films emphasise the previously hidden fourth ‘S’ of tourist marketing – Sex. Papadakis writes that “the myth of Aphrodite emerging from the sunny blue Mediterranean Sea along the coast of Paphos, as used by Greek Cypriots, evokes the three ‘S’s that have become the mantra of tourism marketing: Sun, Sand and Sea”, and he further suggests that Aphrodite’s ‘“seductive qualities” as the Goddess of Love add a touch of romance, as it teases northern European fantasies of the Mediterranean as the land of “Latin Lovers”, and of holidays as opportunities for sex or romance.” [29] Implicit or explicit references to Aphrodite seem to be a recurring theme in Herodotou’s Black Emanuelle films, particularly through the way in which Laura Gemser’s character is introduced in all three films.

Emanuelle: Queen of Sados was mostly shot in Cyprus and the colorful images of Cyprus’ tourist attractions function as one of the key protagonists of the film, as in the case of Vacation in Our Cyprus. The locations are chosen in a way that showcases the beauties of Cyprus, which the characters seem to take pleasure in, while also struggling to make the film appear as a narrative feature film, rather than a series of promotional trailers to market the island’s product of Sun, Sea and Sand. The teenage sexual awakening subplot of Emanuelle: Queen of Sados – for which the film is notorious and which has generated much online speculation about the (unconfirmed) age of actress Livia Russo, who plays the titular character (the film is a.k.a Emanuelle’s Daughter), at the time of shooting – is visually embroidered with the idyllic scenery of Aphrodite’s birthplace at the Rock of Aphrodite in Paphos, while the various Aphrodite-like appearances of Laura Gemser’s Emanuelle challenge other cinematic treatments of the ancient Goddess of Cyprus, which I will discuss in the following section.

Hassanpoulia returns to a pre-nationalist Cyprus to tell the true story of a group of Turkish Cypriot bandits led by Hassanpoulis, a character who acquired a Robin Hood-like quality through various folk narratives that recount the adventures of the legendary bandits in the late 19th century, when Cyprus was still under British administration. The date of the film’s production is key to understanding its counter or subcultural narrative, since shooting was interrupted by the junta-backed coup against Makarios’ government in July 1974, which led to the Turkish military offensive a few days later and the collapse of the Greek dictatorship. Hassanpoulia’s film was again an early example of independent Greek-Cypriot filmmaking based on a collaboration between Greek Cypriots and Greek filmmakers. At the time the Greek members of the production team were contributing to softcore films, which, as noted above, were also read as an underground reaction to the military junta. The Greek junta tried to control politics in Cyprus by supporting the enosis (union with Greece) movement, a political vision that a group of Greek Cypriot hardline nationalists had not abandoned after the island became an independent republic in 1960. The collaboration between Greek Cypriot and Greek filmmakers on the making of Hassanpoulia was also informed by shared anti-junta feelings and Hassanpoulia’s politics, be they incidental or otherwise, may therefore echo Karalis’ description of Greek sexploitation films as a ‘rebellion’ against the junta’s suppression of political freedoms. [30] Pavlos Filippou, who later directed the 1977 film Mavri Afroditi/ Black Aphrodite/ Blue Passion starring the transsexual actress Ajita Wilson, is credited as one of the cinematographers of Hassanpoulia, while Toula Galani portrays the female lead character, Emete, and Viky Konstantinidou participates in one of the sex scenes of the film. Both actresses were famous at the time and frequently starred in Greek erotic films; for example, Toula Galani starred in two Omiros Efstratiadis films and Viky Konstantinidou headlined in a number of popular titles of the time such as Chris Liambos’ Sex…13 Beaufort! (1973).

Demetriou and Herodotou’s efforts are less well-known contributions to European (s)exploitation cinema; however, as alternative forms of Cypriot cinema they set themselves against a uniform filmic paradigm predominantly defined by attempts to represent recent historical events “in order to persuade, explain, or rather – as the Orwellian-sounding phrase goes – to “enlighten (diafotisoun)” others about what really happened and who really is to blame.” [31] This kind of Greek Cypriot cinema was initially steered by the politically motivated introduction of official film policy in 1984 with the creation of the Film Production Council as a division of the Enlightenment Advisory Committee of the Press and Information Office (PIO) of the Republic of Cyprus, which is also responsible for raising awareness about the Greek Cypriot official position on the Cyprus Problem, and implements decisions (in line with the above mission) made by the Advisory Committee on Enlightenment.

Hassanpoulia and Herodotou’s international co-productions share generic and other (e.g. talent) remnants from the post-World War II success of Italian genre films, such as the spaghetti western and the sword-and-sandal epics. The casting of actors such as Gabriele Tinti and Gordon Mitchell in Emanuelle: Queen of Sados, and the theme of the honorable outlaw, who has suffered injustice and becomes the protector of the poor and innocent, in Hassanpoulia reverberate with Italian cinema’s golden age of spaghetti westerns through an obvious attempt to capitalise on already familiar formulas. The allusions to Italian westerns in Hassanpoulia have been jokily noted in an online forum, [32] where Dimitriou’s film is described as a “halloumi-western” (halloumi being a local traditional cheese). In this film, director Kostas Dimitriou reimagines late 19th century Cyprus as a space which is both more unruly and sexier, in contrast with earlier cinematic representations of rural Cyprus by Giorgos Filis – the director of the first Cypriot full length feature film Agapes kai Kaimoi [Loves and Sorrows] (1965) – as a “folk nostalgic paradise.” [33] For example, whereas Filis idealises the traditional Cypriot wedding – a privileged spectacle in his films – Demetriou attempts to ‘celebrate female sexual agency’, as the key female characters, Emete and Marina, “do not hesitate to initiate sexual intercourse outside wedlock.” [34]

Black Emanuelle as Aphrodite’s Corrupted ‘Twin’

Aphrodite, the ancient Goddess of Cyprus, appears frequently in the brief history of Cypriot cinema either as a direct reference to the myth or through the symbolic naming of characters. For example, Aphrodite is the name of the female lead in Panikos Chrysanthou’s Akamas (2006), one of the key fiction films dealing with the Cyprus Problem. Aphrodite is also constructed as the personification of the women subjected to sexual violence during the events of 1974 in Andreas Pantzis’ O Viasmos tis Afroditis/ The Rape of Aphrodite (1985), the first installment of the director’s ‘Aphrodite and Evagoras’ tetralogy. Kamenou writes that the story of the male leading character in The Rape of Aphrodite “‘becomes a vehicle for exposing Turkish violence against “the island of Aphrodite” and, specifically, Turkish sexual violence against Greek-Cypriot women. It is no coincidence that all of the women who were raped and are presented or mentioned in the film are symbolically named “Aphrodite.””’ [35]

Stylianou-Lambert and Philippou observe that “‘the space of the beach and the myth of Aphrodite became increasingly important when promoting Cyprus as a tourist destination and this is reflected in some of the films”’ of the early period of Cypriot cinema. [36] This is also true of the Black Emanuelle films shot in Cyprus, specifically Emanuelle: Queen of Sados and Love Cult, in which the beach is a central locale. It has been noted that the dominant perception of Aphrodite in Cyprus, especially on the part of Greek Cypriots, is of the Goddess of love and beauty, at the expense of her many other personae. [37] Papadakis writes that “‘in an island where according to Greek mythology the goddess was born, the Greeks of Cyprus saw in Aphrodite proof of the island’s primordial Greekness. Like Aphrodite, Cyprus has been Greek since the dawn of history”’. [38] In recent times “Aphrodite has been mostly (ab)used by the Cyprus Tourism Organization (CTO) with an icon of Aphrodite dominating its campaigns, only the graphic based on the statue (in the Cyprus Archaeological Museum) was given porn-star characteristics […] fuller lips, notably enhanced breasts, liposuction in the waist, and more pronounced hips.” [39]

The symbolic treatment of Gemser’s exotic beauty as an Aphrodite-like lethal temptress with a high sex drive can be read against the visual representations of the various Aphrodite-like characters in the cinema of the Cyprus Problem. According to Mendik, whose study focuses on Joe D’Amato’s Black Emanuelle films “‘Gemser’s deathly status was often conflated with her blackness”’; he goes on to explain that D’Amato’s “‘films provide a way into understanding the very specific European fears and contradictions around black sexuality”’. [40] Gemser’s personae in the Cypriot trilogy may reflect Mendik’s discussion of D’Amato’s Black Emanuelle films. However, in addition to Aphrodite, the Goddess of Cyprus has a second, oriental, persona – Ashtart – which can also be equated with the exotic and oriental Emanuelle embodied by Laura Gemser, and this may ‘disturb’ the ethnocentric exploitation of the Goddess’ mythological relationship to Cyprus.

According to local legend, Aphrodite emerged from the sea at Aphrodite’s Rock or the Rock of the Romios in Paphos. One of Gemser’s early appearances in Emanuelle: Queen of Sados is in a shot of her topless, riding a horse in the water on the beach while her husband enjoys the sight from his small private plane, unaware that she has orchestrated his imminent crash as revenge for his sadistic tendencies. Emanuelle then emerges ‘reborn’ from the sea; but she has to sacrifice her freedom in order to take revenge for a second time, this time on the man whom she hired to kill her husband and who goes on to blackmail her and rape her underage stepdaughter (in the film’s most infamous sequence).

Similarly, in Love Cult Gemser plays the spiritual leader of the anti-monogamy cult Children of Light; she appears for the first time bathing in milk on a yacht, guarded by a muscle-man who in the course of the film repeatedly shows off his ability to ‘pec dance’ and executes anyone who decides to leave the cult. Gemser has a sexual encounter with her favorite disciple Dorian (played by the film’s director, Christian Anders) at Aphrodite’s Rock, during the course of which she ecstatically pushes him underwater. In The Dirty Seven, Gemser is first introduced cooling her topless body next to a natural source of water. In the full version of the film (as opposed to the re-edited American home video and television release entitled Emanuelle Queen of the Desert) Gemser’s character appears quite late in the film, after a young woman is gang raped by a group of mercenaries who arrive on the island to carry out a kill mission, and she begins to lure the ‘dirty’ commandos into deadly traps. Thus in both Love Cult and The Dirty Seven, western tourists and unsuspected military ‘invaders’ are disoriented and bewildered by Emanuelle’s otherworldly quality, and are ultimately punished by Emanuelle and the equally exotic realms she inhabits. In contrast to D’Amato’s Emanuelle, whose “body literally becomes invaded by the primitive forces surrounding her”, [41] in these films Gemser’s character both owns and enjoys the bodies that enter her realm – in true Aphrodite fashion.

Conclusion

Michael Given writes that a ‘pure’ narrative of Aphrodite does not exist; the culturally fluid origins of the Goddess have been shaped by imperial suitors and ideological forces. He goes on to observe that accounts informed by an imperial relationship to the island typically corrupt the Goddess in order to demonstrate (unconsciously or otherwise) that the people of Cyprus need and desire to be tamed by an outside force. Similarly, ancient sources usually equated the Goddess of Cyprus’ alternate persona, Ashtart, with repulsion and decadence, and colonialists also exploited this fact to demonstrate that Cyprus and its people were primitive. [42] Gemser’s Aphrodite-like portraits in the Cypriot Black Emanuelle trilogy can be read as a corrupted version of the Goddess, a modern Ashtart whose body is neither a symbolic expression of Turkish violence, nor a vehicle for substantiating the island’s relationship to Greece and not even an idealized perception of love; rather, it is the expression of an unruly non-place or an ideologically empty space that unwittingly disturbs stereotypical manifestations and ideological exploitations of Aphrodite. The films invite a playful reading of Gemser’s Emanuelle as a modern embodiment of the Aphrodite myth. Her final action in Emanuelle: Queen of Sados takes place at the Curium Ancient Theatre, one of the most important archaeological sites in Cyprus and the space in which she kills her stepdaughter’s rapist. On the one hand, this scene is an attempt to echo the Aristotelian exploration of mimesis and catharsis in ancient Greek tragedies, while on the other it is a ‘bad’ performance that unintentionally and playfully trashes the imagined continuities between ancient and modern Cyprus which are annually celebrated through the revivals and modernisations of ancient Greek tragedy that are staged at the same theatre under the Cypriot summer night sky. The Cypriot Black Emanuelle trilogy capitalises both on the success of its predecessors and on the island’s popularity as an idyllic tourist destination, the island of Aphrodite, goddess of love. Black Emanuelle may walk the Goddess’ path, but her nature is not exactly the epitome of romantic love; she is rather a lethal Dea-ex-machina that abruptly resolves the plot of Emanuelle: Queen of Sados and inexplicably kills The Dirty Seven, while in Love Cult ‘in a moment of supreme lust’ she destroys her temple and followers as part of a planned mass suicide that seals the Cypriot Black Emanuelle’s fate as Aphrodite’s corrupted twin.

With thanks to Julian Grainger for research confirming production details relating to some of the films discussed.

Footnotes

- Constandinides, C. and Papadakis, Y. (2014) “Tormenting History: The Cinemas of the Cyprus Problem”, In: Constandinides, C. and Papadakis, Y. (eds) Cypriot Cinemas: Memory, Conflict and Identity in the Margins of Europe. New York: Bloomsbury. 129.

- Kleanthous-Hadjikyriakou, S. (1995) “Istoriki Anaskopisi tou Kypriakou Kinimatografou [A Historical Account of Cypriot Cinema]”, In: Shiafkalis, N. ed. (1995). I Istoria tou Kinimatografou stin Kypro [The History of Cinema in Cyprus]. Nicosia: 7th Art Friends Club. 163-165.

- Constandinides, C. (2014) “Transnational Views from the Margins of Europe: Globalization, Migration and Post-1974 Cypriot Cinemas”, In: Constandinides, C. and Papadakis, Y. (eds) Cypriot Cinemas: Memory, Conflict and Identity in the Margins of Europe. New York: Bloomsbury. 151-180.

- Shiafkalis, N. (ed.) (1995) I Istoria tou Kinimatografou stin Kypro [The History of Cinema in Cyprus]. Nicosia: 7th Art Friends Club. 130-133.

- Dimitriou, A. (ed.) (2000) Strictly Inappropriate: Greek Porn from Omonia to Alkazar (Afstiros Akatallilo: Elliniko Porno apo tin Omonia sto Alkazar). Athens: Oxy.

- Needham, G. (2012) “Greek Cinema without Greece: Investigating Alternative Formations”, In: Papademetriou, L. and Tzioumakis, Y. (eds) Greek Cinema: Texts, Histories, Identities. Bristol: Intellect, 213.

- Shiafkalis 1995.

- Karalis, V. (2012) History of Greek Cinema. New York: Continuum.

- Ibid.

- Karalis. 163.

- Needham. 215.

- Komninou M. and Kassaveti, O. E., (2012) ‘“My Private Life”: An Attempt to Map the Greek Erotic Cinema of 1971-1974” (‘Idiotiki mou Zoe’: Mia Apopira Iconographias tou Ellinikou Erotikou Kinimatografou tis Periodou 1971-1974)”, In: Sarikaki K. and Tsaliki L. (eds). Mass Media, Popular Culture and the Sex Industry (Mesa Epikinonias, Laeki Koultoura kai I Viomihania tou Sex). Athens: Papazisis, 165-200; and Kassaveti O. E. (2014) The Greek Videotape (1985-1990) [I Elliniki Videotainia (1985-1990)]. Athens: Asini.

- Komninou and Kassaveti. 169.

- Ibid.

- Needham,. 213.

- Karalis. 165.

- Needham. 216.

- Karalis. 165.

- See Krzywinska, T. (2005) “The Enigma of the Real: The Qualifications for Real Sex in Contemporary Art Cinema”, In: King, G. (ed) Spectacle of the Real: From Hollywood to ‘Reality’ TV and Beyond. Bristol: Intellect. 223–34.

- Karalis. 166.

- Mathijs, E. and Mendik, X. (2004) “Making Sense of Extreme Confusion: European Exploitation and Underground Cinema”, In: Mathijs, E. and Mendik, X. (eds) Alternative Europe: Eurotrash and Exploitation Cinema Since 1945. London: Wallflower Press. 3.

- Ibid., 4.

- Karalis 2012.

- Ibid..

- Hjört, M. (2010) “Affinitive and Milieu-building Transnationalism: the Advance Party Initiative”, In: Iordanova, D., Martin-Jones, D. and Vidal, B. (eds) Cinema at the Periphery. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press. 49.

- Karalis. 26.

- Stylianou-Lambert, T. and Philippou, N. (2014) “Aesthetics, Narratives, and Politics in Greek-Cypriot Films: 1960–1974”, In: Constandinides, C. and Papadakis, Y. (eds). Cypriot Cinemas: Memory, Conflict, and Identity in the Margins of Europe. New York: Bloomsbury. 80.

- Ibid. 81.

- Papadakis, Y. (2006) “Aphrodite Delights”, Postcolonial Studies, 9 (3), 244.

- Karalis. 168.

- Constandinides and Papadakis. 2.

- Anonymous post on an online forum named Retromaniax, available from: www.retromaniax.gr/vb/showthread.php?20521-%D4%E1-, accessed June 20, 2013.

- Stylianou-Lambert and Philippou. 62.

- Kamenou, N. (2014) “Women and Gender in Cypriot Films: (Re) claiming Agency amidst the Discourses of its Negation”, In: Constandinides, C and Papadakis, Y. (eds). Cypriot Cinemas: Memory, Conflict, and Identity in the Margins of Europe. New York: Bloomsbury. 185.

- Ibid. 184.

- Stylianou-Lambert and Philippou. 75.

- Papadakis 2006 and Given, M. (2002) “Corrupting Aphrodite, Colonialist Interpretations of the Cyprian Goddess”, In: Bolger, D. and Serwint, N. (eds) Engendering Aphrodite: Women and Society in Ancient Cyprus. American Schools of Oriental Research, 419-428.

- Papadakis 2006, 239.

- Constandinides, C. and Papadakis, Y. (2014) “Introduction: Scenarios of History, Themes, and Politics in Cypriot Cinemas”, In: Constandinides, C and Papadakis, Y. (eds). Cypriot Cinemas: Memory, Conflict, and Identity in the Margins of Europe. New York: Bloomsbury, 1-30 (23).

- Mendik, X. (2004) “Black Sex, Bad Sex: Monstrous Ethnicity in the Black Emanuelle Films”, In: Mathijs, E. and Mendik, X. (eds). Alternative Europe: Eurotrash and Exploitation Cinema Since 1945. London: Wallflower Press, 147.

- Ibid. 155.

- Given. (2002).