|

Twelve years ago, British audiences were first introduced to Takashi Miike’s Audition (1999), and it opened the doors to a new genre of cinema that had rarely been seen in national cinemas. The distributor Tartan Films had a reputation for showing difficult, subversive films that championed new directors from around the world and more often than not, they threw down a gauntlet to the censors to challenge existing laws. The company was the natural home of Audition, which on its initial run was not promoted as Asia Extreme. Many critics reviewed it as a horror film, or even a Jacobean tragedy. It took a subsequent number of films in the same genre for a recognisable brand to be built up around them. Emma Pett’s research offers some interesting insights into its perception now some three years after Tartan’s demise and quite rightly, explains that ‘Asia Extreme’ (a brand rather than a ‘distribution label’) is separate to Asian Extreme/ Extreme Asia or whatever general loose terms have previously been used in a wider film business context.

My own interest in Emma’s paper derives from the fact that I was Tartan Video’s Press Officer for an eight year tenure, starting before we had ever encountered Takasi Miike, Hideo Nakata, Kim Ji-Woon and Park Chan-Wook. So alongside Pett’s analysis However, I think it is important to consider the cultural climate for film distribution and exhibition at the time of Asia Extreme’s emergence. The company was one of the leading independent distributors in the UK, who had |

previously released films both theatrically and for home entertainment. With DVDs taking over from VHS as the preferred format, this was a rapidly expanding side to the industry with audiences hungry for product.

The release pattern for the cinema format was different than today, where stiff competition and digital conversion means that that the traditional art-house films can be expected to play for a limited number of days with weekend box office becoming the measure of a film’s success. Equally, many of the independent cinemas had their own in-house programmer who would knew how to nurture their local audience and would be prepared to champion films he/she believed in. Hence a film was frequently allowed to breathe and develop an audience over a number of weeks before it was rested from a cinema’s programme. That same print would then be shared amongst regional cinemas for several months so that it could be four to six months before a film made its first appearance on DVD, but only for rental, its retail release could be a year after it was first shown in cinemas.

During this period, the high street offered a wide selection of outlets as well as rental companies. At the time of Tartan’s initial Asia Extreme titles, the internet and especially Amazon were still in early stages of developing specific audiences. There was also a stronger art house presence in stores such as HMV, Virgin, Borders and WH Smith, as well as in rental stores. It therefore has to be noted that the first wave of films that Tartan released which formed the Asia Extreme brand were not initially labelled as such: Audition, Ringu (Hideo Nakata, 1988), Battle Royale (Kinji Fukasaku, 2000), and The Eye (Oxide Pang Chun/Pang Fat, 2002) for example, were seen as part of the general slate of world cinema release.

The release pattern for the cinema format was different than today, where stiff competition and digital conversion means that that the traditional art-house films can be expected to play for a limited number of days with weekend box office becoming the measure of a film’s success. Equally, many of the independent cinemas had their own in-house programmer who would knew how to nurture their local audience and would be prepared to champion films he/she believed in. Hence a film was frequently allowed to breathe and develop an audience over a number of weeks before it was rested from a cinema’s programme. That same print would then be shared amongst regional cinemas for several months so that it could be four to six months before a film made its first appearance on DVD, but only for rental, its retail release could be a year after it was first shown in cinemas.

During this period, the high street offered a wide selection of outlets as well as rental companies. At the time of Tartan’s initial Asia Extreme titles, the internet and especially Amazon were still in early stages of developing specific audiences. There was also a stronger art house presence in stores such as HMV, Virgin, Borders and WH Smith, as well as in rental stores. It therefore has to be noted that the first wave of films that Tartan released which formed the Asia Extreme brand were not initially labelled as such: Audition, Ringu (Hideo Nakata, 1988), Battle Royale (Kinji Fukasaku, 2000), and The Eye (Oxide Pang Chun/Pang Fat, 2002) for example, were seen as part of the general slate of world cinema release.

|

For audiences and critics alike, this was the first time that such films had been given wide distribution in the UK and understandably, it generated much media interest with newspapers being more disposed editorially to cover non-mainstream cinema, not just by reviewing the films but also running interviews and features that explored the trends. Indeed, they would refer to ‘extreme asia’ as a term that thematically linked them all.

It should also be remembered that Battle Royale was released in the week of 9/11 and despite generally positive reviews in the daily press that compared it with The Lord of the Flies (Peter Brook, 1963) and A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971), it had an impact on audience numbers that were below expectation, leaving it to develop its reputation and cult following in subsequent months, something that Tartan could nurture and develop for its home entertainment catalogue. Considering the company released over 300 DVD titles, it became necessary to distinguish certain styles of films with the discerning cinema fan in mind. Hence there was the general ‘Tartan Video’ brand which included most contemporary independent films regardless of the country of origin; ‘Tartan Terror’ designated horror with its own uniform sleeve look, and ‘The Bergman Collection’ was given distinctive packaging for the discerning collector. ‘Asia Extreme’, therefore, was devised with a similar purpose in mind and it worked for retailers too. |

In those early days, specialist magazines such as Neo and Impact had yet to appear, whilst many of the now popular websites had yet to be created, meaning that reference resources were limited at the very beginning. Up to the start of 2000/ 2001, the main areas of genre Asian cinema that had built a strong ‘fanboy’ following were associated with martial arts and anime. As a company, Tartan’s reputation was already built on showcasing cutting-edge, provocative European films, such as Irreversible (Gasper Noé, 2002), The Idiots (Lars von Trier, 1998), Man Bites Dog (André Bonzel, Rémy Belvaux, Benoȋt Poelyoorde, 1992) and Funny Games (Michael Haneke, 1997) from emerging directors and in turn they had created a brand loyalty from a primarily art-house audience as well as a younger student demographic. These Asian films were complementary for the library which appealed to the discerning collector of world cinema as well as those who sought wilder, dark storytelling. In fact, one of the company’s continually best-selling titles was John Woo’s Hard Boiled (1992), which was a forerunner to many of the high octane actioners that followed.

Tartan had also championed the likes of Wong Kar-Wai alongside one of the world’s greatest stylists: Yasujiro Ozu, but Asia Extreme was devised and marketed to represent a very specific genre of contemporary film from Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Thailand. Whilst Tartan acquired a body of work from these new auteurs from the Far East, some of their work fell outside that definition and was released under the general Tartan Video label. This was the case with Kim Ki-Duk, whose Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter… and Spring (2003) found critical and commercial success with more traditional world cinema audiences, whilst The Isle (2000) and Bad Guy (2001) fitted into the ‘Extreme’ category. In many ways, such branding was comparable with the way that horror films have been given convenient terms such as ‘slasher’ or ‘torture porn’. Indeed ‘extreme’ films such as the non-Tartan title, Grotesque (Kōji Shiraishi, 2009), came out after American films such as Saw (James Wan, 2004) and Hostel (Eli Roth, 2005) had already been criticised for their sadistic violence so arguably, its reputation was judged in the wake of the controversy these American films had initiated.

The Asia Extreme library grew monthly, and the audience appreciation of those titles expanded alongside it, finding particular fan enthusiasm on the increasingly emerging websites. In order to ignite that initial interest though, and in order to establish the brand, the tiles were launched through a touring Asia Extreme festival, which had been devised in conjunction with the Cineworld chain, to screen nine titles for two weeks at a time in various UK cities. Publicity and marketing could then be shaped around the whole event and be extended through to the eventual Video/ DVD releases. A cross-promotional exercise that launched the label, its success led to two subsequent annual roadshows. By that stage, ‘Asia Extreme’ had established itself in the consumer’s mind as well as the media’s.

Interestingly, when looking at the ten titles that Emma has chosen for her survey, over half of them are Tartan titles, and the strongest of these are the films which received a nationwide cinema release. This goes much of the way to explaining why the highest percentages suggest those audiences were viewing the films, in cinemas at least, as an informed choice (from extensive media awareness and advertising) as well as passionate followers of Asian cinema. That is an endorsement of brand loyalty to Tartan’s cinema releases as much as to Asia Extreme itself.

Tartan had also championed the likes of Wong Kar-Wai alongside one of the world’s greatest stylists: Yasujiro Ozu, but Asia Extreme was devised and marketed to represent a very specific genre of contemporary film from Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Thailand. Whilst Tartan acquired a body of work from these new auteurs from the Far East, some of their work fell outside that definition and was released under the general Tartan Video label. This was the case with Kim Ki-Duk, whose Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter… and Spring (2003) found critical and commercial success with more traditional world cinema audiences, whilst The Isle (2000) and Bad Guy (2001) fitted into the ‘Extreme’ category. In many ways, such branding was comparable with the way that horror films have been given convenient terms such as ‘slasher’ or ‘torture porn’. Indeed ‘extreme’ films such as the non-Tartan title, Grotesque (Kōji Shiraishi, 2009), came out after American films such as Saw (James Wan, 2004) and Hostel (Eli Roth, 2005) had already been criticised for their sadistic violence so arguably, its reputation was judged in the wake of the controversy these American films had initiated.

The Asia Extreme library grew monthly, and the audience appreciation of those titles expanded alongside it, finding particular fan enthusiasm on the increasingly emerging websites. In order to ignite that initial interest though, and in order to establish the brand, the tiles were launched through a touring Asia Extreme festival, which had been devised in conjunction with the Cineworld chain, to screen nine titles for two weeks at a time in various UK cities. Publicity and marketing could then be shaped around the whole event and be extended through to the eventual Video/ DVD releases. A cross-promotional exercise that launched the label, its success led to two subsequent annual roadshows. By that stage, ‘Asia Extreme’ had established itself in the consumer’s mind as well as the media’s.

Interestingly, when looking at the ten titles that Emma has chosen for her survey, over half of them are Tartan titles, and the strongest of these are the films which received a nationwide cinema release. This goes much of the way to explaining why the highest percentages suggest those audiences were viewing the films, in cinemas at least, as an informed choice (from extensive media awareness and advertising) as well as passionate followers of Asian cinema. That is an endorsement of brand loyalty to Tartan’s cinema releases as much as to Asia Extreme itself.

|

If Tartan was one of the first distributors to open up that market, it didn’t remain exclusively so, but they were fortunate enough to have many of the seminal titles that have become best associated with the genre. Interestingly, the company’s success bringing commercial success to South Korean cinema in the UK, resulted in a cultural trade conference that wanted to learn how they could expand a greater awareness of Korean culture, so the impact of those initial titles cannot be underestimated.

The films may have been marketed to a specific demographic which was primarily male and under 30, but this was not exclusively the case. However, it developed a more ‘fanboy’ enthusiasm with each subsequent release who were loyally building up their collection with each passing month and arguably Tarantino’s Kill Bill (2003-2004) films ignited new, younger audiences to these Asia Extreme titles, giving them an additional ‘cult’ films status. By nature, it was not unknown for a film that had been made in non-English speaking country to be released a year or two after it had come out in its country of origin. As those audience demand and interest grew, not least their knowledge and awareness of the wider selection of films to view outside of Tartan’s small output, and Amazon’s profile grew, it meant fans could order titles direct from Japan or Korea as soon as they were released, placing Tartan in a position where it was in danger of stockpiling older titles that would increasingly appeal only to UK buyers who never considered importing them. |

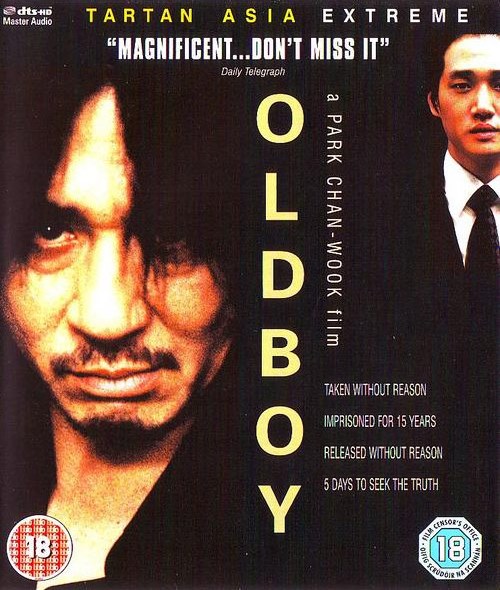

With the commercial success of these films, other distributors could measure the increased demand and so sought to compete for a share of the same audience with their own ‘extreme’ titles with varying degrees of success. Sales agents too recognised the increased market value of their product too and Hollywood woke up to the commercial viability of remaking the most successful such as The Grudge (Takashi Shimizu, 2004), The Ring (Gore Virbenski, 2002) and Dark Water (Walter Sallis, 2005). With Park Chan-Wook’s Old Boy (2013) winning the Palme D’Or at Cannes in 2004, the film became a major box-office success to a much wider audience and greater media attention. Its critical and commercial success helped bring Asia Extreme brand to a wider audience, and that included America, since this was one of the first titles that Tartan released in the US in a belated attempt to replicate the brand over there. With the tragedy of the Virginia Tech Massacre, it was perhaps inevitable someone would want to search for a cause by inciting violence in the media as a cause. In this case, Old Boy briefly develop a notoriety born out of hasty conjecture and the need to generate knee-jerk copy from certain areas of the right-wing press, which some commentators liked to goad as if poking a hornet’s nest with a twig. Battle Royale had originally been banned outright in the States in the wake of the Columbine high school massacre that had occurred in 1999, and in Japan too the film had been the subject of much controversy which prompted new legislation on censorship so that it was restricted to the over 16s. That reputation followed the film to the UK and created much of the debate in the press, starting some six months before the film actually screened in cinemas.

In general, it can be said that the die-hard Asia Extreme fans could be classified as fanboys, in much the same way that devotees of sci-fi, horror or even westerns might be. Their passion for the genre means they become early adopters my near dint of devoting more time to their favourite area of entertainment, and in some case, were quick to become leading experts and commentators. For those who answered the Tartan questionnaire that accompanied each of our releases, it is fair to say that these films appealed to those with an active interest in art-house cinema, willing to explore new filmmakers from a diverse range of countries, but they would be more selective of what titles from the range they would watch. Since many of those participating in the survey were unhappy defining themselves as fans of Asian Extreme. I suspect their response is less based on discomfort, but more a rejection of being forced to choose a label for their tastes. A discerning fan of world cinema or indeed other areas of entertainment such as music or literature is likely to want to explore the widest range of subjects and filmmakers, but wishing to follow through in the body of work from a particular auteur. Much is to do with the negative perception of the label ‘fanboy’. After all it is not a term that is applied to someone who had an obsessive passion for Hitchcock or film noir or queer cinema. As the survey reveals, the largest group of respondents preferred Hollywood and non-mainstream films, the more traditional arthouse market. Furthermore, the most significant age range falls between 26-35 age group expressing more discerning tastes. This is a reflection on the more general audience that supported independent and non-English language films.

That’s not to say, Tartan never labelled its target audiences; indeed, it embraced the idea of a fan base for Asia Extreme, who were predominantly the younger student group, ensuring that there were new titles released every month, as well as special editions or retail incentives to invest in the whole range. However, this was never the exclusive audience and the reputation of a handful of titles meant they had standing as exemplary examples of world cinema. This was reflected in the media coverage that the films received too. For example, Battle Royale was reviewed in national and regional newspapers, specialist film magazines, as well as music, style and gay press. It even found favourable responses in magazines such as GQ, Heat and OK! That broad level of readership reach is scarcely niche.

In terms of a gender demographic for these titles, as with horror films, there was a noticeably high appreciation amongst women with critics and audiences alike sharing a similar enthusiasm. These were also a group that loved horror films but also had a much more eclectic taste. Attendances at Frightfest and Edinburgh International Film Festival, for example, proved that these were regarded as event movies and would play to packed auditoriums. Considering the number of respondents who are under 25, it suggests they have discovered the films after their initial release in part if not completely due to their lasting, even cultish reputation, since they would not have been old enough to watch them at the time. It is indicative of the phenomenal success of the ‘Asia Extreme’ brand that it remains as potent as ever alongside the other genre-inspired definitions of J-horror and K-horror. Indeed, contrary to comments that it was short-lived commercial success, the lead titles remained best-sellers right up to the point of Tartan’s eventual collapse. Park Chan-Wook’s films were some of the first blu-ray releases too. True, the number of new releases had become irregular but then so had the company’s investment in the brand which, on reflection, seems to really cover a particular genre of films that were being made within a ten-year period (c1999 - 2006).

Of course, I do wonder how these films would be treated now if we were encountering them for the first time. There is now such a variety of platforms for showcasing films, including downloads, pay-per-view channels, and internet sales portals, cinemas have increasingly become competitive on a commercial level, high street outlets are diminishing and the contraction of media outlets, it would be more difficult to generate the same audience reach but it wouldn’t diminish the power and originality of these energising, innovative filmmakers and there will always be people who want to explore new avenues of cinemas, people who will always think out the box.

In general, it can be said that the die-hard Asia Extreme fans could be classified as fanboys, in much the same way that devotees of sci-fi, horror or even westerns might be. Their passion for the genre means they become early adopters my near dint of devoting more time to their favourite area of entertainment, and in some case, were quick to become leading experts and commentators. For those who answered the Tartan questionnaire that accompanied each of our releases, it is fair to say that these films appealed to those with an active interest in art-house cinema, willing to explore new filmmakers from a diverse range of countries, but they would be more selective of what titles from the range they would watch. Since many of those participating in the survey were unhappy defining themselves as fans of Asian Extreme. I suspect their response is less based on discomfort, but more a rejection of being forced to choose a label for their tastes. A discerning fan of world cinema or indeed other areas of entertainment such as music or literature is likely to want to explore the widest range of subjects and filmmakers, but wishing to follow through in the body of work from a particular auteur. Much is to do with the negative perception of the label ‘fanboy’. After all it is not a term that is applied to someone who had an obsessive passion for Hitchcock or film noir or queer cinema. As the survey reveals, the largest group of respondents preferred Hollywood and non-mainstream films, the more traditional arthouse market. Furthermore, the most significant age range falls between 26-35 age group expressing more discerning tastes. This is a reflection on the more general audience that supported independent and non-English language films.

That’s not to say, Tartan never labelled its target audiences; indeed, it embraced the idea of a fan base for Asia Extreme, who were predominantly the younger student group, ensuring that there were new titles released every month, as well as special editions or retail incentives to invest in the whole range. However, this was never the exclusive audience and the reputation of a handful of titles meant they had standing as exemplary examples of world cinema. This was reflected in the media coverage that the films received too. For example, Battle Royale was reviewed in national and regional newspapers, specialist film magazines, as well as music, style and gay press. It even found favourable responses in magazines such as GQ, Heat and OK! That broad level of readership reach is scarcely niche.

In terms of a gender demographic for these titles, as with horror films, there was a noticeably high appreciation amongst women with critics and audiences alike sharing a similar enthusiasm. These were also a group that loved horror films but also had a much more eclectic taste. Attendances at Frightfest and Edinburgh International Film Festival, for example, proved that these were regarded as event movies and would play to packed auditoriums. Considering the number of respondents who are under 25, it suggests they have discovered the films after their initial release in part if not completely due to their lasting, even cultish reputation, since they would not have been old enough to watch them at the time. It is indicative of the phenomenal success of the ‘Asia Extreme’ brand that it remains as potent as ever alongside the other genre-inspired definitions of J-horror and K-horror. Indeed, contrary to comments that it was short-lived commercial success, the lead titles remained best-sellers right up to the point of Tartan’s eventual collapse. Park Chan-Wook’s films were some of the first blu-ray releases too. True, the number of new releases had become irregular but then so had the company’s investment in the brand which, on reflection, seems to really cover a particular genre of films that were being made within a ten-year period (c1999 - 2006).

Of course, I do wonder how these films would be treated now if we were encountering them for the first time. There is now such a variety of platforms for showcasing films, including downloads, pay-per-view channels, and internet sales portals, cinemas have increasingly become competitive on a commercial level, high street outlets are diminishing and the contraction of media outlets, it would be more difficult to generate the same audience reach but it wouldn’t diminish the power and originality of these energising, innovative filmmakers and there will always be people who want to explore new avenues of cinemas, people who will always think out the box.