..the visually erotic element pervaded all genres of cinema from comedy to drama without exception. At the same time, cinematographic censorship policies were slowly discarded… the result triggered a prosperous development of erotic cinema… (today surprisingly experiencing a revival known as “Italian trash cinema.”)” [1]

Rėmi Fournier Lanzoni Comedy Italian Style: The Golden Age of Italian Comedy Films

Introduction

As indicated above, the liberalisation of censorship and changing social mores during the 1970s meant that erotica began to permeate all genres and aspects of the Italian film industry, with startling and unsettling effect. Although this process continued into the 1980s, it has widely been presumed that a later retrenchment of the commercial film industry, coupled with the consequent need for television co-productions functioned as the key determinants that motivated the return to a blander, more universally acceptable fare. However, recent critical interventions (that includeing Lanzoni’s comic studies as well aslongside the Glynn, Lombardi and O’Leary’s collection Terrorism Italian Style: Representations of Political Violence in Contemporary Italian Cinema) have begun to more fully consider how the turbulent political and social contexts of 1970s Italy also affectedeffected the filoni’ (or popular film cycles) produced during this period. To this extent, we would argue that markedly differing renditions of erotica between the 1970s and 1980s can be seen as much of a response to the wider social and political tensions of the period as it was to transitions in industry and production practices.

In this essay we will examine two filoni (cycles) that placed particular emphasis on the erotic – the sex comedy and morbid erotic drama – to explore how these films constituted both a reflection of and a response to broader socio-political tensions and transformations of the period. The focus of our examination will be the erotic filoni produced by Dania Film, arguably the largest and most significant producer of popular genre films to emerge in Italy in the post-war period. The essay constitutes the first output of a broader research project looking into Dania Film and its productions, funded by the University of Brighton’s Rising Star award. The project draws on a range of resources (such as the company’s archives, records and film catalogue) in order to consider how Dania’s output from the 1970s and 1980s can be linked to not only nascent production and industry practices, but also the wider political and social uncertainties of the period.

Luciano Martino and Dania Film

As indicated above, the liberalisation of censorship and changing social mores during the 1970s meant that erotica began to permeate all genres and aspects of the Italian film industry, with startling and unsettling effect. Although this process continued into the 1980s, it has widely been presumed that a later retrenchment of the commercial film industry, coupled with the consequent need for television co-productions functioned as the key determinants that motivated the return to a blander, more universally acceptable fare. However, recent critical interventions (that includeing Lanzoni’s comic studies as well aslongside the Glynn, Lombardi and O’Leary’s collection Terrorism Italian Style: Representations of Political Violence in Contemporary Italian Cinema) have begun to more fully consider how the turbulent political and social contexts of 1970s Italy also affectedeffected the filoni’ (or popular film cycles) produced during this period. To this extent, we would argue that markedly differing renditions of erotica between the 1970s and 1980s can be seen as much of a response to the wider social and political tensions of the period as it was to transitions in industry and production practices.

In this essay we will examine two filoni (cycles) that placed particular emphasis on the erotic – the sex comedy and morbid erotic drama – to explore how these films constituted both a reflection of and a response to broader socio-political tensions and transformations of the period. The focus of our examination will be the erotic filoni produced by Dania Film, arguably the largest and most significant producer of popular genre films to emerge in Italy in the post-war period. The essay constitutes the first output of a broader research project looking into Dania Film and its productions, funded by the University of Brighton’s Rising Star award. The project draws on a range of resources (such as the company’s archives, records and film catalogue) in order to consider how Dania’s output from the 1970s and 1980s can be linked to not only nascent production and industry practices, but also the wider political and social uncertainties of the period.

Luciano Martino and Dania Film

By way of introduction to this wider study of Dania Film, it is appropriate to provide a preliminary overview of the key personalities behind the organisation. Pivotal to the success of the company was producer Luciano Martino, who was himself born into a cinematic family. His grandfather Gennaro Righelli was the director of numerous important films, including Italy’s first sound film, La canzone dell’amore (1930). Luciano Martino first entered into the cinema in 1954 (at age 21) as an assistant to Luigi Zampa, but quickly moved into scriptwriting, contributing to numerous films for directors like Raffaello Matarazzo, Sergio Corbucci, Umberto Lenzi, Domenico Paolella and Mario Bava. He produced his first film, Il demonio/ The Demon (Brunello Rondi) in 1963 before founding his first company, Devon Film, in 1964. In partnership with Mino Loy he produced a number of influential films for Zenith Cinematografica as well as co-directing three films with Loy between 1964 and 1966. Although he was to direct four further films in his life, it was as a producer that he really made his name, through a series of closely linked companies, all of which operated out of the same offices and are really only distinct for economic and legal reasons. The best known of these, Dania Film, produced 111 films between 1973 and 2012. But Dania was proceeded by the aforementioned Devon Film (1964-1987, 29 titles) and the short-lived Lea Film (1971-1973, 11 titles) and followed by Nuova Dania (1977-1984, 21 titles). The latest manifestation of the company, Devon Cinematografica, was founded in 1983 and is still-operational; since Luciano’s death in 2013, it has been run by his two daughters, Dania and Lea (who lent their names to the companies) and has thus far produced 9 titles. All told, the companies produced some 170 titles, plus at least 22 films and series for television since 1982. [2]

Dania Film (and from hereon we will use the name as an umbrella term to refer to all of these companies), remained a close-knit family affair. The initial CEO was Luciano’s mother, Lea, while his younger brother, Sergio, was to become the company’s most trusted director, shooting 37 films and 14 television productions for the company between 1969 and 2008, in virtually every genre. Luciano’s cousin, Michele Massimo Tarantini, also became a reliable hand directing 13 films for the company, primarily comedies, before relocating to Brazil in the mid-80s.

In the early 1970s the French-Italian-Maltese actress Edwige Fenech and the Urugayan George Hilton became the company’s regular on-screen couple beginning with an influential series of gialli directed by Sergio Martino (which are arguably the most significant contribution to the genre outside of Dario Argento’s films). Hilton was to marry Tarantini’s sister, thus gaining Italian citizenship and entering into the Martino family, while Fenech was to form a decade-long personal relationship with Luciano. Under the direction of Sergio and Mariano Laurenti (another key Dania filmmaker, with 15 films to his credit), Fenech was to become one of the defining icons of popular Italian cinema in the 1970s before virtually retiring from acting and reinventing herself as a producer at the end of the 1980s.

From the Suggestive to the Successful: Dania’s Template at the Box-Office

So why was Dania Film so successful? Undoubtedly one reason was Luciano’s canny ability to identify audience tastes and adapt standard generic forms to fit the zeitgeist. In so doing, Dania became one of the key exponents of the ‘filone’ system, through which a single commercial-hit would produce a prolific but short-lived cycle of close imitations before the cycle exhausted itself and a new breakout-hit spawned the next filone. Luciano played a key role in codifying and popularising the giallo with Il dolce corpo di Deoborah/ The Sweet Body of Deborah (1968 Romolo Guerrieri) and Così dolce, così perversa/ So Sweet… So Perverse (1969, Umberto Lenzi) – both co-produced with Mino Loy for Zenith Cinematografica – and the four films directed by Sergio Martino and starring Hilton and Fenech. He also made a considerable contribution to the spaghetti western (14 titles between 1968 and 1987) and the ‘poliziesco’ (‘cop film’; 10 titles between 1973 and 1984), with key contributions to virtually every other filone exploited at the time, including the cannibal and the mondo cycles. Perhaps his biggest contribution, however, was to the ‘commedia scollacciata’ (sex comedy), which he effectively invented, with no less than 38 titles in the decade 1972 to 1982. This cycle was launched by the huge success ofQuel gran pezzo dell’Ubalda, tutta nuda tutta calda Ubalda (AKA All Naked and Warm [1972, Mariano Laurenti]), the first of a series of ‘decamerotici’ or medieval erotic comedies that proliferated in the early part of the decade and which also included Dania’s La bella Antonia, prima monica e poi dimonia (also 1972 and directed by Laurenti and starring Fenech).

While such medieval erotic movies indicated Dania’s ability to accommodate the 1970s Italian interest in historically themed erotica, 1973 saw them move into more contemporary examinations of sexuality with Sergio Martino’s Giovannona Coscialunga, disonorata nell’onore/ Giovannona Long-Thigh, This film proved influential for adding the vague promise of nudity or eroticism to the generic structure of the farce. In so doing, Giovannona Long-Thigh was to become the defining title of the sex comedy genre and to indelibly mark an entire generation in Italy. Both these films were conceived as populist responses to celebrated works by ‘auteur’ filmmakers. Th:e the first was to Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Trilogy of Life (1971-1974), which had transgressed censorship boundaries, generated controversy and enjoyed an unexpected and unprecedented commercial success; the latter (at least in its title) was to Lina Wertmuller’s Mimi metallurgico, ferito nell’onore/ The Seduction of Mimi (1972), a comic drama set against the background of left-wing politics, organised crime, Southern Italian migration and female emancipation. Both films testify to Luciano’s ability to capitalise on innovations in ‘serious’ cinema, tapping into the zeitgeist and constituting easily replicable cycles of popular films.

A second element of these film’s success (and that of Dania as a whole) is in the titles, which are at once highly suggestive and playfully ironic (Ubalda, All Naked and Warm could just as easily apply to a porn film). Coupled with eye-catching and titillating poster artwork (whose concept derived – like the titles – from Luciano himself), which exaggerated and emphasised the physical attributes of Fenech:

Using this vocabulary of exaggerated excess, these films became both iconic and emblematic of an entire period in Italian cultural history. But their enduring appeal also offers some explanation of why these texts were so emblematic of the social and political climate of the time, which also warrants further analysis.

The Sex comedy and the Shocking Seventies Zeitgeist

From the late-Sixties through to the early-Eighties, Italy witnessed a range of dramatic social upheavals and transformations. The so-called Economic Miracle saw Italy transformed from a primarily agrarian economy to a manufacturing based consumerist society, while per capita income increased faster than any other European country: from 100 to 234 between 1950 and 1970. [3] These changes were more marked in the North, causing massive internal migration (over 9 million people between 1955 and 1971), [4] which had an enormous socio-cultural impact, in particular on the more traditional South. For example, the percentage of regular church-goers in Italy declined from 69-40% from 1956-1968. [5] The rapidity of these changes can perhaps partly account for the political polarisation of the late 1960s, which saw an increasing adherence to far-left and far-right parties, coupled with an explosion of political violence that lasted throughout the ‘anni di piombo’ (Years of Lead) of the 1970s. As Rėmi Fournier Lanzoni has noted:

For Italy, the decade (1969-1980) brought an unprecedented series of setbacks as extremist political violence became part of … life and affected the face of a nation with significant human loss… [6]

No less significant than the political turmoil of the period however, were the changes to gender roles in a country which, as the decade dawned, remained highly conservative and Catholic in outlook. During this period, women began to occupy a more central role in the economic and political sphere, with female employment rising by nearly 50% between 1970 and 1985 at a time when male employment remained stagnant. [7] Under the influence of feminism, traditional sexual mores and conceptions of womanhood began to be challenged, as evidenced by the legislative changes that took place during this period: the prohibition of female adultery was repealed in 1968, divorce was legalised by Law 898 in 1970 and ratified by means of a controversial referendum in 1974 in which 60% of Italians voted in favour, while abortion was legalised in May 1978 following a 1975 referendum prompted by over 700,000 signatures collected by feminist activists.

Paradoxically, however, these progressive changes were accompanied by a dramatic increase in the ‘consumption’ of female sexuality facilitated by the declining influence of the Catholic Church and liberalisation of censorship. Although Italian cinema had long alluded to unabashed images of female sensuality, changes in social mores coupled with a gradual weakening of censorship restrictions meant that sex was to become both more central and explicit during this period. While the passing of Law 161 in 1962 theoretically meant that films would only be censored if either individual scenes or the entire film offended ‘good taste’ (as per article 21 of the Constitution), in reality a dramatic change in practice did not take place immediately. [8] Nevertheless, the hundreds of denunciations and seizures that took place throughout the Sixties and early Seventies should be read not as evidence of the persistence of the value system of earlier decades, but rather as an ultimately doomed attempt to stem the tide of changes during a period of dramatic transition. The release of the first erotic publication for men in 1966 was the first step in a process that would lead inexorably to the opening of the first ‘red-light’ cinema screening hard-core pornography in Milan a decade later, on the 15 November 1977.

Cab Drivers, Cops and Carnal Tutors: Sexual Mobility in the 1970s Sex Comedy

Arguably the Italian filone responded to the rapid social and legal changes affecting women’s status within Italy by representing them as desirable but ultimately disruptive figures in the range of Dania sex comedies that proliferated in the era. These sexual contradictions were particularly played out for humorous effect in titles which charted the impact of female interventions into previously male dominated social spheres. For instance, the success of Steno’s comedy La poliziotta [The Policewoman] (1974), which dealt with the disruption caused by a young woman (Mariangela Melato) appointed to the police force after she out performs her male counterparts, sparked Luciano Martino’s imagination and initiated one of his most prolific and successful comic cycles. Specifically, this generated a long series of films in which a young and attractive woman (usually played by Edwige Fenech) enters into a typically male-dominated workplace and in so-doing upsets the established (patriarchal) order.

In the six years between 1975 and 1981 Dania produced no less than fourteen films in this ‘professional woman’ filone – three policewoman sequels, two soldier films, two nurse films, two doctor films, four teacher films and a single taxi driver film – while a further seven entries in the series were furnished by other companies. The comedy in these films alternates between the difficulties the female character experiences in fulfilling her role and the effects that the presence of a desirable female character has on the surrounding male characters. A good example would be La soldatessa alla visita militare (1977, Nando Cicero) in which Edwige Fenech’s character takes up a position as a doctor within a military barracks as a proteststatement against the discrimination which prevents women from doing military service (this was only passed in 1999, making Italy the last of the NATO countries to allow voluntary service for women). The barracks is inevitably populated by a gallery of sexually-frustrated, borderline abnormal types, such as the character played by Dania regular Alvaro Vitali, who is driven into paroxysm and compulsive masturbation by the slightest sexual thought and as a result repeatedly and unwittingly finds himself in borderline homosexual situations. The arrival of Fenech thus provides a catalyst for the break-down of the fragile equilibrium of this male world.

Despite their extremely formulaic nature and their bawdy unsophisticated humour, these films nonetheless constitute perhaps the most explicit and sustained consideration of the impact of changing gender roles and employment practices in Italian cinema of the period. Moreover, when viewed chronologically, we can observe a progression towards a gradual acceptance and normalisation of the woman’s presence within the workplace. Yet for many critics, any possibility of an ideologically progressive reading of this narrative is negated by the voyeuristic impulse displayed when Edwige Fenech takes over the role from Mariangela Melato and Luciano Martino morphs the straight comedy of La poliziotta into the sex comedy. For example, Gian Piero Brunetta argues that the “the dominant logic [of the sex comedy] is to obtain a collective regression to the pleasure of voyeurism, to the emotion of spying through the keyhole, to the sense of sin committed solely through the act of desiring.” [9] Yet this analysis downplays the extent to which the films render explicit this act of voyeurism by doubling the spectatorial gaze through the presence of desiring and frustrated voyeurs within the narrative, not to mention the presence of literal spying-through-the-keyhole shots in films such as Luciano Martino’s own La vergine, il toro e il capricorno/ Erotic Exploits of a Sexy Seducer (1977). Moreover, we should not underestimate the fact that – as in the example just cited – the spectatorial surrogate is typically an incompetent or infantilised male, often embodied by the rubber-faced, middle-aged comic Alvaro Vitali, expanding on a role he first fulfilled in Fellini’s Amarcord (1973). Indeed, it is significant that Vitali’s screen persona as the sexually frustrated male voyeur would be perpetuated across much of his career, particularly through the 30-plus films he made for Dania having signed an exclusive contract with them in 1975. These films thus mock the voyeuristic (male) spectator, inviting him to laugh at his own frustrated desire in a process of recognition and self-critique. If this is the case, then these films can be considered not the debasement of the great tradition of the commedia all’italiana (Comedy Italian Style) as many have argued, but rather the displacement of this genre’s characteristic process of inviting the spectator to identify with and laugh at a series of negative social stereotypes onto the plane of the erotic.

Moreover, this voyeuristic impulse is frequently inextricably bound up with a wider discourse about the conflict between changing gender roles and the liberalisation of sexuality and the institutions of social, political, religious and patriarchal authority. For example, the extraordinary credit sequence of Taxi Girl – in which Fenech again assumes a masculine profession in emulation of her father, despite the complaints of her traditional Southern Italian fiancé – contains a sustained 21 second close-up of her naked breasts against a backdrop of well-known sights as she drives her taxi through the centre of Rome having been divested of her clothes in a comic pre-credit sequence. While this sequence undoubtedlyinarguably serves the function of titillation, the juxtaposition of naked breasts with landmarks such as St Peters means that this sequence cannot be considered solely an objectification of the female form for the pleasures of the (male) viewer as part of a calculated commercial operation. Rather, it is also an explicit – and amusing – commentary on the tension between the contradictory processes of liberation/repression that characterise the period. While Fenech’s character is not nude by choice in this scene, she nonetheless makes no attempt to cover herself and shows no shame at her nudity, in defiance of the Catholic and Conservative conceptions of female sexuality explicitly evoked by the presence of St Peters in the background. This interpretation chimes with that of Giuseppe Turroni (writing in 1979 at the height of the sex comedy cycle but shortly before the release of Taxi Girl). Here, the (transgressive) presence of a sexually desirable woman within these institutions proves a destabilising force that upsets the normal order to comic effect. But the sexual availability of these women is typically only apparent and the desire it provokes in her male counterparts is constantly frustrated by the woman’s denial of their advances. Thus, according to Turroni, in the sex comedy (unlike pornography), the tension between desire and repression reveals the continued possibility of choice and reaffirms the significance of the reproductive act. [10] While, as Manzoni and Menarini note, [11] we should be wary of pushing this line of argument too far and offering a counter-interpretation of the cycle as some kind of feminist and libertarian intervention, it is equally true that a straight feminist critique of the films as reactionary objectification of the female form is equally simplistic. Rather, the films embody the complicated tension between the progressive and the reactionary, the emancipated and the objectified, revealing the ambivalence and ambiguities within the collective Italian psyche of the period.

Arguably, the use of Edwige Fenech’s star persona to convey the sexual contradictions of 1970s Italy were equally imprinted on the ‘Schoolteacher’ films that became aligned with Dania between the years of 1975 and 1978. As indicated by the Martino-produced L’insegnante/ The School Teacher (1975, Nando Cicero), sex comedy tropes were frequently fused with wider social concerns around the role of emancipated Italian womanhood in an era of decreased male influence and increasing countercultural agitation. In this respect, later sequels to the cycle such as L'insegnante va in collegio/ (AKA The School Teacher Goes to Boys High (Mariano Laurenti, 1978) remain particularly significant for their comic incorporation of contemporary terrorist fears into the sexploitation template. This title pairs Fenech’s habitual role as a desirable mentor with an industrialist’s attempts to evade threats from trade uUnionists and militants alike. Having declared himself bankrupt, this so-called “Captain of Industry” (played by genre regular Renzo Montagnani) relocates to a provincial town, where both he and his teenage son fall for Fenech, who plays the lone female language tutor at an all-male Catholic college. In the film’s finale the thwarted industrialist inadvertently reveals his true identity just in time for the local left wing terrorist faction to ship him off for an extended period of incarceration as the heroine begins to seduce his son. This unsettling finale itself proves significant, echoing Alan O’ Leary’s recent work on Italian filone cinema and 1970s terrorist tensions. Here, the trope of cross-generational conflict remains at the core of comic productions produced during the terrorist years precisely because they function as “an index of a society decidedly out of joint.” [12]

Social and Sexual Immobility in the Dania Erotic Drama

While Dania’s 1970s erotic ventures employed comic tropes to comment on an emergent Italian female mobility, the company’s 1980s output morphed into far darker reflections on female interventions into an increasingly unstable political sphere. In these later productions, the trope of the socially attuned and (apparently) sexually voracious Italian woman was recast as a potentially vengeful and threatening figure, whose potency sharply contrasted with the images of male disability, incarceration or criminal internment that populated these works.

Befitting this far more melancholic mode of narrative, it seems significant that Dania’s 1980s erotic content replaced the vivacious and jovial performances of Edwige Fenech with far more complex and contradictory representations of female desire, embodied by performances from actresses such as Monica Guerritore. Often appearing with (her then husband) Gabriele Lavia as a co-star and director, it was not uncommon for the actresses’ performances to take on a vengeful and even monstrous element. These unsettling images once again reflected wider social trends and tensions that the Dania canon so skilfully managed to exploit.

For critics such as Ruth Glynn, the 1980s shift towards representing Italian female protagonists as violent and even sexually unhinged cannot be divorced from the widerfearthat emerged as the country took stock of more than a decade of terrorist activity. Writing in the study ‘Terrorism: A Female Malady’, Glynn argues that violent insurrection remained “not just a phenomenon of the very recent past… but an ongoing reality from which Italy was only tentatively beginning to emerge” during the 1980s. [13] While these continued atrocities were evidenced by bombings and assassinations perpetrated by both right wing cells and leftist extremists, Glynn also identifies a process of pentitisimo, where captured protestors gained state reductions for their crimes by naming collaborators. These trials not only kept the traumatic memories of terrorism within the public sphere, but “for the first time, shed light on the full extent and the nature of women’s involvement in acts of terrorism.” [14]

Arguably, the new public knowledge surrounding female participation in terrorist inspired violence seeped into both the public consciousness and popular culture of the1980s, producing films that functioned as “narratives of ongoing collective and cultural trauma.” [15] According to Glynn, these celluloid fears were reproduced in a range of fictions which equated female sexuality to acts of violence or terrorism, whilst also revealing women as a potential threat to ‘normalised’ family relations. Although not as explicitly political as the two case-studies which form the basis of the author’s analysis, Dania’s erotic output from the 1980s does provide similarities to draw strong parity with the twin tropes of the femme fatale and the sexually unstable woman that the author discusses.

For instance, Gabriele Lavia’s 1986 erotic entry Sensi/ (AKA Evil Senses) exemplifies the first of Glynn’s trope in its use of a range of film noir devicses to punctuate a dark political thriller about a former hitman Manuel Zani (Gabriele Lavia) being pursued by a lethal female assailant Vittoria (Monica Guerritore), who has disguised herself as a high class escort. From its outset, where Zani is forced to flee his London home down a back alley (framed via high angled and off-kilter camerawork that dwarfs him against the exterior stairwell to the building), Evil Senses employs stylistic and thematic tropes associated with film noir to convey the protagonist’s fatalistic entrapment at the hands of the duplicitous female lead. In so doing, the visual components of the scene reproduce what J.A. Place and L.S. Peterson have defined as a thriller format that is used to “unsettle, jar, and disorient the viewer in correlation with the disorientation felt by the noir heroes.” [16] Further, the film’s credit scene theme tune entitled ‘We’ll Die Together’, which is played out over a montage of Zani fleeing to a safe-house in Rome establishes the equation of carnality with threat, which functions throughout the remainder of the film. These morbid sexual themes are established in an early sexual encounter between the pair, when Manuel insists on covering Vittoria’s face with a linen sheet before caressing her masked features, giving the impression that the dark heroine is in fact a decaying cadaver encased in a death shroud. Noting the historical connection between film noir’s dark heroines and the later Italian erotic dramas of the 1980s, Ruth Glynn argues that:

…the myth of the femme fatale functions here not only as a male fantasy articulating and exorcising a fear of the violent woman, but also… signals that Italian culture is still desperately seeking to exorcize the fears, and work through the trauma, of the anni di piombo. [17]

As applied to Dania’s erotic output of the 1980s, Glynn’s comments appear pertinent, as Evil Senses conveys these twin traumas at both cinematic and historical levels. At the level of style and thematic configuration, the film betrays its debt to noir traditions (with pivotal sex scenes between the couple even being juxtaposed against oversized art murals of American handguns to underscore the ‘hard-boiled’ basis of their carnality). The meticulous plotting of Vittoria’s deception over the central male further echoes traits associated with 1940s thrillers such as Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944). Here, the introduction of a much older ‘husband’ replicates the classic dark romance structure of noir, where an ill-fated male attempts to usurp the sexual position of a more established rival in order to achieve illicit sexual union. However, the introduction of Evil Senses’ older surrogate suitor speaks more to the film’s historical traumas than its cinematic influences. As we discover, Vittoria’s ‘husband’ is in fact a shadowy benefactor, who is stage managing her ‘seduction’ of Manuel in order to extract political documents from the hero prior to his assassination. As Manuel himself explains, having opened a concealed dossier containing the names of men who fund his career as a hitman, these identities were ultimately revealed as “Respectable people, honourable men, men above suspicion.” Thus, the second traumatic level of Evil Senses links it more fully to the consideration of anni di piombo narratives that Glynn discusses, where widespread fears of violence were often attributed to anonymous social elites and shadowy governmental forces.

If Dania’s 1980s erotic thrillers do draw on the fears of sexually emancipated women who “dominated the cinematic exploration of terrorism and its effects” [18], then it remains the project of these texts to limit or counter the impact of their influence, even at the cost of narrative coherence. Arguably, these formal tensions are evidenced in the finale of Evil Senses, when Vittoria reveals her true affections towards Manuel, thus defying her employer’s request to eliminate him. Manuel’s response to the heroine’s final proclamations of emotion is to suddenly shoot her in the forehead. The closing images of the film then focus on her fatal head wound, while the hero narrates a professional and personal rationale for his violent actions.

As with the case-studies Ruth Glynn has explored, the uncharacteristic ending to Evil Senses “signals that the myth of the femme fatale functions here not only as a male fantasy articulating and exorcising a fear of the violent woman, but also as a wider cultural fantasy articulating and exorcising a fear of terrorism.” [19] The figure of the violent Italian woman further haunts the narrative of Scandalosa Gilda/ Scandalous Gilda, which Dania released a year earlier in 1985. This film acts very much as a companion piece to Evil Senses, once again pairing Monica Guerritore1 and Gabriele Lavia onscreen, with the latter also adopting the role of director for Luciano Martino’s company.

Although not as explicitly political in its exploration of the cinematic/historical traumas as Evil Senses, the film retains an overwhelming air of erotic morbidity, leading film critic William Bibbiani to define it as a “surprisingly dark erotic “thriller”’ which provokes “an uneasy feeling of sickening aberration” in its viewer. [20] The film’s transgressive focus revolves around the degenerateive sexual bond between a mysterious and emotionally unstable female (Guerritore) and a laconic comic strip artist (Lavia), who meet during a random road encounter after the heroine has been spurned by an unfaithful husband. As with the couple’s later film for Dania, Scandalous Gilda uses established thriller themes and formal devices to convey the ambiguous sexual and moral intentions of its heroine. At an iconographical level, this film noir flavour is conveyed in the film’s pre-credit scene, where the concealed heroine watches her husband engage in a slow motion tryst with his lover, before palpationspalpitations of disgust lead to the couple to discover her presence. Here, Guerritore is shot from a low angle to convey her menacing intent, while her costume of the favoured noir attire (black fedora, shades and raincoat) instantly conveys the complex and carnal attributes of her character. In so doing, the scene recreates the iconographical features of the classic noir universe, namely the “visually unstable environment in which no character has a firm moral base". [21]

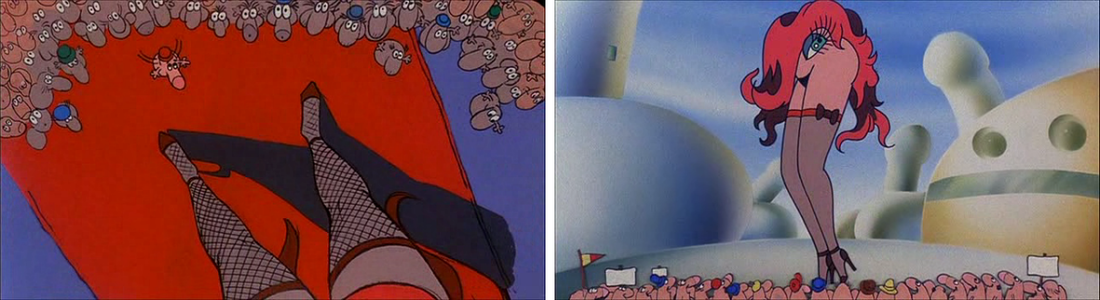

While the heroine’s ambiguous potential remains comparable with some of noir’s most iconic dark heroines (not least the character’s more mainstream and celebrated namesake played by Rita Hayworth in King Vidor’s 1944 production of Gilda), she also evidences what Ruth Glynn would term as “overt and unbridled sexuality, a key characteristic of the femme fatale.” [22] These destructive urges are conveyed with disturbing intensity in the heroine’s erotic encounters with Lavia’s character, which incorporate increasingly punishing scenarios of erotic humiliation and assault, abduction and ultimately death. The domineering role that the heroine adopts in relation to these taboo acts is conveyed both via her physical performance, as well as via a surreal animated insert that emerges from Lavia’s attempts to reproduce the couple’s emergent romance in comic strip form. The resultant graphic art insert remains significant for providing a fantasised vignettescape that further promotes the heroine’s sexual dominance over male characters within the narrative. Here, the animated female is conveyed as an erotically oversized presence that tantalises, taunts and then wounds the literally dwarfed male members that gather around her in hopes of sexual conquest:

While the use of such animated inserts reiterate the threatening potential of the eroticised woman from Dania movies pairing Monica Guerritore with Gabriele Lavia, they were also reproduced in other films that the actress completed for Luciano Martino. Central to these further renditions of dark eroticism remains her role in Dania’s controversial release Fotografando Patrizia/ (AKA The Dark Side of Love) from 1984. The film was directed by noted erotic auteur Salvatore Sampiri, and functions as an unofficial remake of his earlier Grazie zia/ (AKA Come Play with Me), which was released in 1968 at the height of political unrest in Europe. The earlier film located an incestuous relationship between the physically and mentally unstable teenager Alvise (Lou Castell) and his sexually unfulfilled older aunt (Lisa Gastone) against a backdrop of student rebellion and the Vietnam war. Here, news reportage and atrocity re-enactment frequently interrupt the erotic games between the two, establishing morbid overtones that result in sexual regression and ultimately death.

The Dark Side of Love revisits these themes of politics and polymorphous sexuality via the transgressive coupling played out between the 16-year-old Emilio (Lorenzo Lena) and his older sexually precocious sister Patrizia (Guerritore). Indicating its basis in trauma rather than titillation, it is noticeable that The Dark Side of Love begins and ends with images of death and regression. The opening scene depicts the funeral of Emilio’s mother and is intercut with his obsessive reviewing of home video tapes revealing the infantilising degree of control the deceased matriarch exercised over him. As we discover, Emilio suffers from a severe bone deformity which has in the words of one character “trapped his body between childhood and manhood”, a permanent state of physiological regression that forces Patrizia to return from her career as a fashion designer in Venice in order to tend him. These early scenes function to establish initial distinctions between the pair, indicating that Emilio embodies regression via a morbid bond to the dead mother and the archaic surroundings of the house (which his sister frequently dismisses as dust-ridden and suffocating). By contrast, Patrizia initially signifies not interiority, but the world ‘outside’, specifically an Italy increasingly dominated by both feminine and transnational influences. Ultimately, this new Italy is revealed as a world of artifice, which embodies fashion, consumption and Americanised influences (as indicated in Patrizia’s attempts to court ill-informed overseas investors into her business dealings).

While The Dark Side of Love initially splits its siblings along these interiorised/external markers, sexual tensions soon come to the surface to efface such distinctions. The moral decline between the pair is initiated when Patrizia begins to organise a series of sexual encounters for her brother to watch, thus exploiting his desire to view taboo acts. Patrizia’s controlling actions confirm the second strategy of female sexual subversion that Ruth Glynn has identified in her analysis of 1980s popular Italian narratives. Here, direct references to the fears associated with the anni di piombo are replaced by a transgressive focus on the dark carnal drives of the Italian woman as a threat to sexual normalcy. Echoing the links to implied threat that underpins these taboo acts, it is noticeable that Patrizia frequently refers to her own body in abject and violent terms, even commenting that as a woman “Your vagina fills you with shame, much worse than robbery, mugging and murder.” These referencesinferences to violation and death are themselves figured in the film’s closing scene when the heroine’s final acts of sexual experimentation with her brother render the regressive circuit is complete, with the film ending on an unsettling image of the pair wrapped in a foetal death pose.

To this extent, The Dark Side of Love, as well as the other Dania productions we have surveyed indicate Italian popular cinema’s ability to use erotic tropes to reflect wider industry trends and social tensions. Arguably, the films produced by Dania Film are not underpinned by an ‘intellectual’ agenda and do not articulate an explicit or coherent position with regard to politics, sexuality and gender roles. Rather, within the constraints of the filone system and, thanks to Luciano Martino’s remarkable insight, they function rather like ‘instant movies’, capturing and refracting social changes of the time. While their position is undoubtedly inconsistent and often ambivalent, it is these very qualities that make them such a clear barometer for the psychic tensions of the period. In many ways they can be likened to Robin Wood’s ‘incoherent texts’, [23] which fail to present a consistent ideological position and instead reveal the ambiguities, fault lines and tensions of their times. While both the erotic comedies and dramas employ eroticised images for commercial purposes and often objectify their female stars, they also complicate straightforward voyeuristic viewing positions and highlight a weakened and fractured sense of masculinity that make them among the most revealing films of the social, sexual and psychological tensions and transitions of 1970s Italy.

Footnotes

- Fournier Lanzoni, R. (2008) Comedy Italian Style: The Golden Age of Italian Comedy Films. New York: Continuum, 157.

- Data derived from an analysis of the production lists contained in Bernardini, A. (ed.) (1990) Archivio del cinema italiano. III. Il cinema sonoro 1970-1990. Rome: Anica.

- Ginsborg, P. (1990) A History of Contemporary Italy: Society and Politics 1943-1988. London: Penguin, 239.

- Ibid., 219.

- Ibid., 245.

- Lanzoni, 139

- Ginsborg 1990: 410.

- Baldi, A. (2002) Schermi proibiti: la censura in Italia: 1947-1988. Venice: Marsilio.

- Brunetta, G. P. (1993) Storia del cinema italiano. Volume quarto: Dal miracolo economico agli anni novanta 1960-1993. Rome: Editori Riuniti, 424.

- Turroni, G. (1979) Viaggio nel corpo. La commedia erotica nel cinema italiano. Milan: Moizzi, 8.

- Manzoli and Menarini 2005: 414.

- Ibid., 54.

- Glynn, R. (2012) “Terrorism, a Female Malady” in Glynn, R. Lombardi, G. and O’Leary, A. (eds), Terrorism Italian Style: Representations of Political Violence in Contemporary Italian Cinema. London: Igrs Books, 118.

- Ibid., 119.

- Ibid., 120.

- Place, J. A. and Peterson, L.S. (1976) “Some Visual Motifs of Film Noir” in Nichols, B. (ed) Movies and Methods. Berkeley: University of California Press, 333.

- Glynn, 126-127.

- Ibid., 120.

- Ibid., 126.

- Bibbiani, W. (2010) “Scandalous Gilda (review)” in https://www.geekscape.net/geekscape-after-dark-reviews-scandalous-gilda-1985, 2. (Accessed 15th November 2015).

- Place, J. A. and Peterson, L.S., 338.

- Glynn, 128.

- Wood, R. (2003) Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan… and Beyond. New York: Columbia University Press, especially 71-62.