Introduction

Discussing the recent discovery in a Seattle warehouse of the lost negative of his 1978 film, Blue Sunshine, writer-director Jeff Lieberman commented: “Of the five features I’ve made, Sunshine is definitely the most certified ‘cult’ movie, by critics and cinema writers anyway.” The reason Lieberman cites for this: “It’s the one most ‘time-stamped’ to represent a very specific time in American culture.” [1] With respect to Lieberman, we might nonetheless attribute the term ‘cult’ to at least two more of his films, Squirm (1976) and Just Before Dawn (1981). It is those films that I will focus on initially here, with consideration given afterwards to Blue Sunshine. Lieberman was Guest of Honour at 2014’s Cine Excess VIII; I conclude this essay with a reflection on Lieberman’s festival Q&A, and his participation in the industry panel, Cult Crowdfunders: New Audiences, New Funders and the Cult Indie Scene. Before that, however, by way of introduction to Lieberman’s work, a brief consideration of Lieberman’s cult status may indeed serve useful. A broader discussion of what constitutes cult cinema is beyond the scope of this piece, so my analysis will necessarily rely on some common definitions.

Jeff Lieberman as Cult Auteur

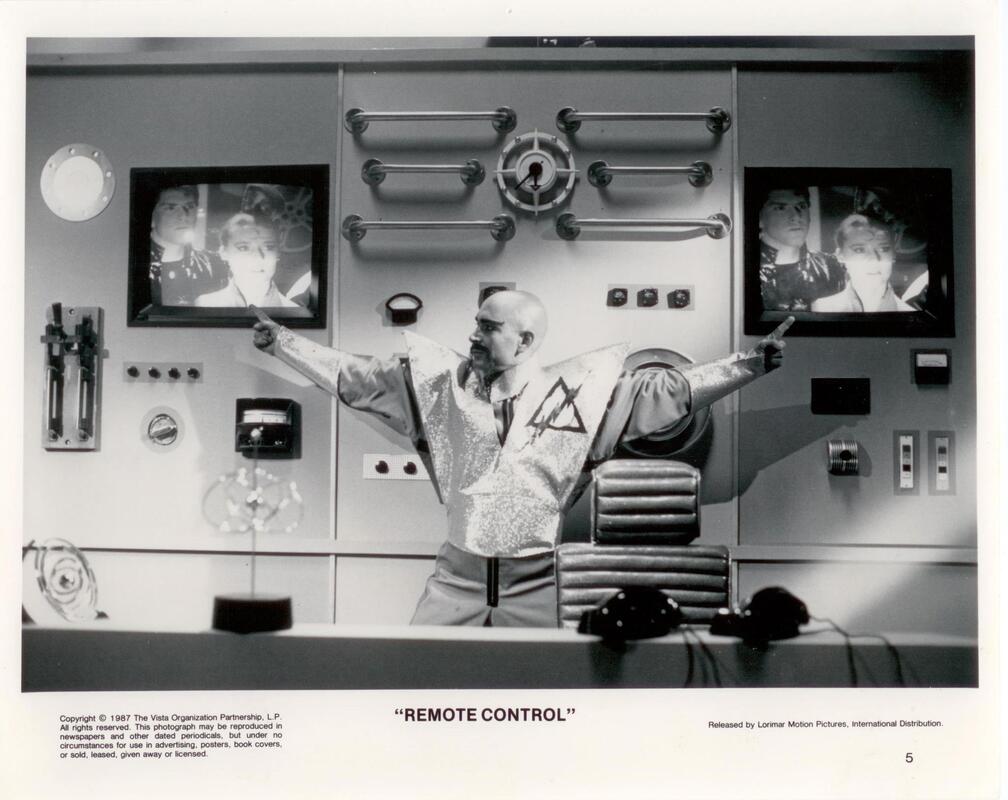

Although not as widely recognised as, say, Romero, Craven or Cronenberg, Lieberman’s films have extended and enriched sub-genres within horror cinema. Squirm is considered one of the best of the 70s cycle of ecological horror films derived from Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963); Blue Sunshine spans the zombie-satire gap between Cronenberg’s Shivers (1975) and Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978); Just Before Dawn (1981) develops and subverts the tropes of Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) and Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes (1977); in its depiction of videotape as modern folk devil, Remote Control (1988) invites comparisons with Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983); and Satan’s Little Helper (2003) riffs intriguingly on Carpenter’s Halloween (1978). Lieberman has the ability to crystallise the essence of a horror sub-genre in a single striking iconographic image:

Discussing the recent discovery in a Seattle warehouse of the lost negative of his 1978 film, Blue Sunshine, writer-director Jeff Lieberman commented: “Of the five features I’ve made, Sunshine is definitely the most certified ‘cult’ movie, by critics and cinema writers anyway.” The reason Lieberman cites for this: “It’s the one most ‘time-stamped’ to represent a very specific time in American culture.” [1] With respect to Lieberman, we might nonetheless attribute the term ‘cult’ to at least two more of his films, Squirm (1976) and Just Before Dawn (1981). It is those films that I will focus on initially here, with consideration given afterwards to Blue Sunshine. Lieberman was Guest of Honour at 2014’s Cine Excess VIII; I conclude this essay with a reflection on Lieberman’s festival Q&A, and his participation in the industry panel, Cult Crowdfunders: New Audiences, New Funders and the Cult Indie Scene. Before that, however, by way of introduction to Lieberman’s work, a brief consideration of Lieberman’s cult status may indeed serve useful. A broader discussion of what constitutes cult cinema is beyond the scope of this piece, so my analysis will necessarily rely on some common definitions.

Jeff Lieberman as Cult Auteur

Although not as widely recognised as, say, Romero, Craven or Cronenberg, Lieberman’s films have extended and enriched sub-genres within horror cinema. Squirm is considered one of the best of the 70s cycle of ecological horror films derived from Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963); Blue Sunshine spans the zombie-satire gap between Cronenberg’s Shivers (1975) and Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978); Just Before Dawn (1981) develops and subverts the tropes of Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) and Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes (1977); in its depiction of videotape as modern folk devil, Remote Control (1988) invites comparisons with Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983); and Satan’s Little Helper (2003) riffs intriguingly on Carpenter’s Halloween (1978). Lieberman has the ability to crystallise the essence of a horror sub-genre in a single striking iconographic image:

In Blue Sunshine we have the murderous baby sitter stalking her young charges with a large knife; her invasion-metamorphosis is signified by her bizarrely bald head, her ‘possession’ by the visual reference to Rosemary’s Baby (1968). In Just Before Dawn, Lieberman’s heroine fends off her backwoods attacker by thrusting her fist down his throat – a gender subversion of the rape/violation imagery redolent of the urbanoia film (most notably the gun-in the-woman’s-mouth scene in The Hills Have Eyes [1977]). In Squirm, we have three such iconic moments, neatly encapsulating the three stages of narrative progression in the apocalyptic horror film as identified by Charles Derry in Dark Dreams 2.0: A Psychological History of the Modern Horror Film [2]: proliferation – the scene where worms infest the face of the antagonist, Roger; besiegement – where the worms threaten to erupt from a showerhead on to the heroine (also, a sly nod to Psycho [1960] – linking via The Birds to Hitchcock); and annihilation – when the worms invade the house and finally engulf Roger, who sinks into them like a man disappearing into quicksand.

The limited availability of his films in the UK in the days before home video and DVD conversely helped cement Lieberman’s cult status in this country in the 70s/80s. While Squirm was a hit (one particular cinema in London’s Piccadilly Circus played it for an entire year), Blue Sunshine and Just Before Dawn both suffered distribution problems in Britain on first release. The Rank Organisation kept Just Before Dawn sitting on the shelf for over a year before burying it in a double-bill with Tyburn’s The Ghoul (1975). Blue Sunshine was never shown in UK cinemas, or on VHS PAL video or, as of yet, on UK-region DVD/Blu-ray (Warner Brothers own the domestic rights). Meanwhile, Lieberman was championed by the likes of Alan Jones and Kim Newman, House of Hammer, Starburst and Fangoria; and film tie-in novelisations of Squirm and Blue Sunshine proved popular with horror fans even while access to the films themselves remained limited. However, Lieberman’s films now enjoy repertory screenings in cultural hubs such as London’s ICA and the New Beverly Cinema (owned and programmed by Quentin Tarantino) in Santa Monica; and Lieberman himself is a regular guest of honour at horror film festivals internationally, participating in Q&As in person or via Skype, helping to expose more fans of the genre to his films through his personal appearances at such events. We can thus see Lieberman’s currency as a cult auteur continuing into the digital age, with his films considerably less ‘rare’ but still ‘specialist’.

Lieberman’s work is often celebrated for its quirky originality and allegorical themes that critique dominant ideologies. This may be why the director himself attributes Blue Sunshine as his “most certified ‘cult’ movie”. By contrast, both Squirm and Just Before Dawn, in their depictions of backwoods rural communities, are more precariously balanced between mocking and reinforcing cultural prejudices. “I am a baby boomer,” Lieberman stated in an interview with Rue Morgue magazine in 2011.

The limited availability of his films in the UK in the days before home video and DVD conversely helped cement Lieberman’s cult status in this country in the 70s/80s. While Squirm was a hit (one particular cinema in London’s Piccadilly Circus played it for an entire year), Blue Sunshine and Just Before Dawn both suffered distribution problems in Britain on first release. The Rank Organisation kept Just Before Dawn sitting on the shelf for over a year before burying it in a double-bill with Tyburn’s The Ghoul (1975). Blue Sunshine was never shown in UK cinemas, or on VHS PAL video or, as of yet, on UK-region DVD/Blu-ray (Warner Brothers own the domestic rights). Meanwhile, Lieberman was championed by the likes of Alan Jones and Kim Newman, House of Hammer, Starburst and Fangoria; and film tie-in novelisations of Squirm and Blue Sunshine proved popular with horror fans even while access to the films themselves remained limited. However, Lieberman’s films now enjoy repertory screenings in cultural hubs such as London’s ICA and the New Beverly Cinema (owned and programmed by Quentin Tarantino) in Santa Monica; and Lieberman himself is a regular guest of honour at horror film festivals internationally, participating in Q&As in person or via Skype, helping to expose more fans of the genre to his films through his personal appearances at such events. We can thus see Lieberman’s currency as a cult auteur continuing into the digital age, with his films considerably less ‘rare’ but still ‘specialist’.

Lieberman’s work is often celebrated for its quirky originality and allegorical themes that critique dominant ideologies. This may be why the director himself attributes Blue Sunshine as his “most certified ‘cult’ movie”. By contrast, both Squirm and Just Before Dawn, in their depictions of backwoods rural communities, are more precariously balanced between mocking and reinforcing cultural prejudices. “I am a baby boomer,” Lieberman stated in an interview with Rue Morgue magazine in 2011.

I was in the drug culture of the ‘60s and I saw everything first hand. I was at Woodstock. I did acid. Marched against the war in Vietnam. Saw Easy Rider. I was immersed in all that in New York. I was at the right place at the right time, at the vanguard of all that stuff. However, I have an innate cynicism so I don’t ever really buy into anything. [3]

Lieberman’s films are markedly intertextual. They invite comparisons with other films in the genre, consciously play with and subvert genre tropes and reference and/or invoke cultural myths (Blue Sunshine, for example, satirises 1970s anti-drug hysteria; Remote Control sends up the 1980s video revolution.) As commented in 1977 by Edgar Lansbury and Joseph Beruh, the producers of Squirm and Blue Sunshine: “Lieberman has a good grasp of the genre and great respect for it.” [4] Whereas Just Before Dawn offers a spin on the survivalist tropes of Deliverance (1972), Squirm and Blue Sunshine belong firmly in the canon of seventies apocalyptic horror identified by Robin Wood in his seminal 1979 essay, ‘The American Nightmare’. [5] Wood considers the American horror films to have entered its apocalyptic phase after 1968, reflecting the ideological crisis and destabilisation that beset America during the time of the Vietnam War and leading to Nixon’s resignation following the Watergate scandal in 1974. According to Wood, the revenge of nature film (of which Squirm is a distinguished example) forms a tangential subgenre within apocalyptic horror. It speaks of anxieties concerning the rape of the environment by corporate-capitalism, and its generic roots can be found in the cold war monsters-caused-by-radiation of 1950s science fiction.

Radiation Movies

Lieberman’s films, including Squirm, are heavily influenced by 50s sci-fi. “As a kid, I thought I was shrinking”, he has recalled of seeing Jack Arnold’s classic The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), “because government was instilling this fear of radiation – you can’t imagine how they frightened my generation with this radiation”. [6] Lieberman’s project can be identified as subverting the ideology of the 1950s sci-fi movie as defined by its outward projection of fears instilled by governments. In his lecture, ‘Radiation Movies’, given at the Miskatonic Institute of Horror Studies in 2011, Lieberman outlined his modus operandi, stating that the atomic age anxieties of the 1950s gave way to government-induced fears of the effects of LSD in the early 1970s and then later the effects of environmental pollution. Throughout the years he has continued to employ the basic story telling formulae of the early sci-fi ‘radiation movies’, whilst simultaneously challenging the messages of those movies and adapting them to the changing times.

Squirm

The fear of ecological disaster underpins Squirm - albeit in a satirical way. In the film, an electricity pylon collapses and ‘electrifies’ a harvest of carnivorous bloodworms which go on to crawl amok through a backwoods Southern town, feasting on the various inhabitants. Lieberman wrote the script in a frenzied six weeks, after putting it off for two years due to family commitments. He sold the script immediately to producers Lansbury and Beruh, who, on the strength of the script, allowed him to direct. Lieberman considers Squirm to be his ‘on the job training’ in directing, and learned to make Squirm, as he said, “one shot at a time”. [7] It became his crash course in the exigencies of low budget film-making. Squirm cost $420,000 to make and was shot in 25 days.

Many reviewers rightly identify Squirm as character-led, that the revenge of nature plot motif is secondary to a portrait of small-town tensions. Reminiscent of the Melanie-Mitch subplot in The Birds, events in Squirm are kicked off by the arrival of a stranger in Fly Creek who arouses the suspicion of the locals. Played by Don Scardino, Mick is a nerdish city-slicker, visiting his girlfriend Geri who lives on the outskirts of town. When bodies of worm victims are found, distrust falls – implausibly - on Mick. He and Geri are forced to investigate the killings themselves and then try to save the disbelieving townsfolk from the marauding polychaetes. Finally it is the small-mindedness of the townsfolk, as much as the threat from the worms, which brings about the demise of the town.

With its Georgia setting and its broad Southern accents, there is more than a little ersatz-Tennessee Williams in Squirm. (Intriguingly, the film was originally set in New England, which perhaps explains the film’s rather Lovecraftian US poster; Lieberman changed the locale at the behest of the producers.) The repression within Geri’s family, characterised by her neurotic mother, and in the townsfolk generally, evokes the Southern Gothic of Williams, but also: the worms themselves represent the eruption of that all-consuming repression, which is brought to a head by Mick’s arrival. A crucial moment in the film concerns Roger, the ‘hick’ who is secretly smitten by Geri and therefore resentful and jealous of Mick. After a scuffle on board a boat where he tries to kiss Geri, Roger falls into a box of bait worms which burrow into his face. Later, Roger is literally consumed by the worms when they infest the house. In the same scene, Geri’s mother is shown to have been consumed also, with only the shell of her body left. Repressing the writing of Squirm for two years due to family commitments may well be one of the things that helped to give the film its queasy power: Squirm feels very much like an outpouring of the young director’s own stifled creativity.

Critics have commented on the film’s often sardonic representation of class, social mobility and North/South difference. Mick, an antiques dealer, is also in Fly Creek to buy up the townsfolk’s family heirlooms, invoking the resentment of the locals who are loath to see their riches go into the pockets of a city boy outsider. In the words of reviewer, Frank Collins, Mick is a “capitalist Yankee ransacking the remains of the South”. [8] Naturally the young people - Mick, Geri and her liberal pot-smoking sister, Alma - face antagonism from the local right-wing sheriff as they attempt to solve the mystery in Scooby-Doo fashion. Lieberman both plays up to and undercuts these stereotypes. Roger is a pathetic figure as he tries to win Geri’s affection through misguided displays of his white, working class masculinity, which is starkly contrasted by Mick’s middle-class preppy-ness. Squirm’s representation of Southern small-town folk is complicated by the fact that Lieberman switched the locale of the story before filming commenced, necessitating a quick script rewrite, leading perhaps, to its heightened sense of pastiche. Lieberman’s characters are written, and played, as broad. This may, of course, also be part of the film’s cult attraction. Squirm certainly does not fall into the ‘so bad it’s good’ category of cult cinema – on the whole the film is competently made and acted – however, there are sufficient elements of ‘badness’ in it to help position it as cult viewing. R. A. Dow’s performance as Roger, for example, like that of Zalman King as Jerry Zipkin in Blue Sunshine, is excessive. Of course, it is important to note that Lieberman deliberately approaches Squirm as a comedy. Its tongue is firmly in cheek, and this suggests that, as a representation of the South, it should not, in the final analysis, be taken too seriously.

Squirm was a huge financial success thanks to the distributor, American International Pictures, promoting it as a creature feature. Although not the first of the 70s ‘nature attacks’ films – Frogs (1972), Night of the Lepus (1972), Phase IV (1974) and Bug (1975), among others, preceded it – Squirm’s primacy revived this flagging cycle in the mid-70s and inspired numerous imitators – The Savage Bees (1976) , Day of the Animals (1977), Empire of the Ants (1977), Kingdom of the Spiders (1977). Although he described the revenge of nature films as generally less interesting and productive than other types of apocalyptic horror, Robin Wood praised Squirm for its underlying familial and sexual tensions à la The Birds, and Lieberman freely acknowledges his debt to Hitchcock in this respect.

Just Before Dawn

Just Before Dawn came into being when, in 1980, Lieberman received a phone call from Czech producer, Doro Vlado Hreljanovic, offering him a script called The Last Ritual. Lieberman agreed to direct on the proviso that he be allowed to completely rewrite the screenplay (under the pseudonym Gregg Irving), retaining only the names of the characters and the basic ‘kids in the woods with a murderer’ premise. Just Before Dawn, then, can be seen as an attempt to work within, and to some extent subvert, the conventions of the 70s urbanoia film, and Lieberman brings his customary intelligence and genre savvy to its run-of-the-mill premise. In the film, campers in the wild are terrorised by a family of machete-wielding killers; only one of them survives, by drawing on her own animal instincts.

Lieberman’s film highlights the survivalist aspects of the story, emphasising the conversion from passive victim to savage survivor of the female character. In his foreword to my book, Subversive Horror Cinema, Lieberman discusses Just Before Dawn’s gender subversion in the following terms:

It was my homage to Deliverance (1972), which had a similar impact on me as Lord of The Flies (1963), and dealt with very similar socio-political issues. I set out to make the Jon Voight character from Deliverance a woman, ‘Connie,’ who would make the same character arc from helpless milquetoast to animalistic survivor. So my political statement if you will was a radically feminist one, to show that when humans are reduced to their animalistic genetic baseline, there was little difference between male or female. Connie became the ultimate ‘final girl,’ long before that term was coined. [9]

Just Before Dawn is often compared to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and The Hills Have Eyes as an urbanoia text, but in many ways can be seen as a riposte to the rape/violation imagery of those films. In Chain Saw Pam and Sally are symbolically penetrated by meat hook and chainsaw; in the Hills Have Eyes Brenda is forced to her knees and orally violated with a handgun. Just Before Dawn both references and subverts this type of iconography in Connie’s final fatal oral fisting of her backwoods attacker. Lieberman presents the action from the point of view of the male onlooker – played by Greg Henry – whose gaze mirrors that of the film’s audience witnessing the audacious gender reversal. The sequence stuns the contemporary viewer because the usual trope of male violator/violated female found in 70s urbanoia is turned on its head. Despite its radical sexual politics, however, the film’s representation of the hillbillies is ambivalent, generally lacking the tongue-in-cheek factors that characterised Squirm.

Just Before Dawn and Urbanoia

James Rose usefully defines the urbanoia film in Beyond Hammer: British Horror Cinema Since 1970. [10] Urbanoia, according to Rose, deals explicitly with the conflict between present and past, rural and urban. The arrival of a group or family of white middle class characters into the wilderness sets off a collision between cultures. This culture clash instigates the events that follow as the group or family are hunted down and killed one by one by their backwoods antagonists as they plunge deeper into the unfamiliar wilderness. As the number of survivors from the urban group diminishes, it is the seemingly weakest group member who finds him or herself galvanised into violent action, drawing on inner resources and animal cunning to outwit and finally hunt down the hunters.

In Just Before Dawn the backwoods clan is stereotypically portrayed as impoverished, primitive, inbred and morally degenerate. Incest has resulted in many instances of congenital freakishness, including the killer hillbillies who are revealed in the film as identical twins. A group of white middle class campers intrude on the wilderness family’s domain, here to visit land inherited from their parents. Rose further defines the conflict between the wilderness clan and the urban group in urbanoia texts as agrarian versus capitalist; the hillbilly figure in these films is presented both as a savage aggressor against the white middle class urban intruders and victim of the economic inequality that exists between city and countryside. The rural ‘have-nots’, in urbanoia tales, are eventually exterminated by the urban ‘haves’ for daring to rise up against the privileged class.

The campers in Just Before Dawn trail their urban sensibilities into the wilderness: they travel in an expensive Winnebago that allows them their material comforts, Blondie’s Heart of Glass blaring on the radio; all the trappings of modernity. One of the characters aims his camera at twin girls who play in the wreck of a car at the side of the road. Dressed in rags, these are, by contrast, children of the historically dispossessed, evoking Dorothea Lange’s famous portraits of rural poverty in the Great Depression. Immediately the group hit a deer, and this foreshadows the events to come; their intrusion into the wilderness constitutes, in the words of George Kennedy in the film, a “shock to nature’s delicate balance”. To underline this theme, Lieberman cuts to a close up of a frightened horse seemingly unsettled by the unwelcome presence of the campers. Kennedy’s forest ranger is a familiar figure in urbanoia, a harbinger and intermediary between civilisation and the wilderness. His warnings to the youngsters, of course, go unheeded.

An urbanoia film, according to Rose, “usually ends with the death of the wilderness patriarch, leaving the sole survivor of modernity to stumble back to the city, bloody and traumatised”. [11] In Just Before Dawn, Connie bears the signs of traumatic rebirth despite her new found empowerment, and through her abjection she ultimately becomes at the end of the film both warrior and matriarch. The final symbolic image of Just Before Dawn takes place at sunrise: Connie stands triumphant over the body of the hillbilly she has defeated, while her terrified boyfriend clings to her like a weeping child.

Lieberman uses the Oregon locations masterfully to build suspense and create atmosphere. The landscape exterior is an essential part of the urbanoia film, as Rose points out: its narrative function to “place the protagonists within a space that initially offers them an escape from their daily experience but eventually isolates them from any sense of modern society in the face of mounting terror”. [12] Lieberman imbues Just Before Dawn with the sheer beauty of nature in the lush, verdant forests and glistening waterfalls of the Oregon mountains, but we are all too aware of the horrors that lurk beneath the canopy of the woods and under the surface of Silver Creek. Lieberman’s final message seems to be that Mother Nature, despite her beauty, is cold, brutal and primordial, and those who seek her solace must be willing to locate the primal within themselves.

Blue Sunshine

Blue Sunshine takes its title from the fictitious strain of LSD which, in the film, turns its users into bald-headed psychotic zombie killers a decade after it is taken. A further example of Lieberman’s ‘radiation cinema’, Blue Sunshine draws on the same government-instilled anti-drug hysteria of the early 1970s that prompted The Ringer, Lieberman’s public information film sponsored by the Coca Cola company in 1972.

An urbanoia film, according to Rose, “usually ends with the death of the wilderness patriarch, leaving the sole survivor of modernity to stumble back to the city, bloody and traumatised”. [11] In Just Before Dawn, Connie bears the signs of traumatic rebirth despite her new found empowerment, and through her abjection she ultimately becomes at the end of the film both warrior and matriarch. The final symbolic image of Just Before Dawn takes place at sunrise: Connie stands triumphant over the body of the hillbilly she has defeated, while her terrified boyfriend clings to her like a weeping child.

Lieberman uses the Oregon locations masterfully to build suspense and create atmosphere. The landscape exterior is an essential part of the urbanoia film, as Rose points out: its narrative function to “place the protagonists within a space that initially offers them an escape from their daily experience but eventually isolates them from any sense of modern society in the face of mounting terror”. [12] Lieberman imbues Just Before Dawn with the sheer beauty of nature in the lush, verdant forests and glistening waterfalls of the Oregon mountains, but we are all too aware of the horrors that lurk beneath the canopy of the woods and under the surface of Silver Creek. Lieberman’s final message seems to be that Mother Nature, despite her beauty, is cold, brutal and primordial, and those who seek her solace must be willing to locate the primal within themselves.

Blue Sunshine

Blue Sunshine takes its title from the fictitious strain of LSD which, in the film, turns its users into bald-headed psychotic zombie killers a decade after it is taken. A further example of Lieberman’s ‘radiation cinema’, Blue Sunshine draws on the same government-instilled anti-drug hysteria of the early 1970s that prompted The Ringer, Lieberman’s public information film sponsored by the Coca Cola company in 1972.

Blue Sunshine is first and foremost socio-political satire playing on the paranoia of post-Watergate America. It amalgamates elements of 70s conspiracy thriller (Executive Action [1973], The Parallax View [1974], Three Days of the Condor [1975]), 60s-type psychedelic drug movie à la Corman’s The Trip (1967), and the invasion-metamorphosis narratives of 50s science fiction (the seminal text here being Invasion of the Body Snatchers [1956]). In Blue Sunshine the protagonist, Jerry Zipkin, goes on the lam after becoming the prime suspect in a murder committed by a friend suffering the psychotic effects of the drug. Investigating the crime himself with the help of his girlfriend Alicia, Zipkin discovers that old college associate Ed Flemming, now a politician, is trying to cover up his past as the drug dealer who sold his friends the experimental ‘Blue Sunshine’. The film builds to a confrontation between Zipkin and Flemming’s bald and berserk henchman, Mulligan, in a discotheque and shopping mall, symbolising the new age of rampant consumerism that the baby-boomers - having compromised the ideals of the 1960s for their own gain – have helped to usher in.

Lieberman had originally set the film in New York, with elaborate flashback sequences showing the characters’ college days; however, for budgetary reasons he ended up cutting those scenes and transposing the story to Los Angeles. In many ways that transposition helps the film. In Shivers and Rabid (1976) Cronenberg emphasises the brutalist architecture of Montreal as a dehumanising influence on the characters; in Blue Sunshine Lieberman uses the sterile modernity of Los Angeles, with its endless shopping centres and boutique malls, to similar effect, providing an ironic backdrop to the drug burn-out narrative. Indeed the intertexuality of the Cronenberg films and Blue Sunshine is underlined by the similarity of several key scenes in the work of both directors: in Blue Sunshine, Jerry anxiously watches his friend, Dr Blume - whom he thinks might be LSD-‘infected’ – perform surgery on a woman with cancer. The suspense is partly generated by Lieberman’s playing on the audience’s genre expectations: a similar scene appears in Rabid, in which a surgeon succumbs to the rabies virus while working on a patient and turns homicidal in the operating theatre.

Blue Sunshine’s central suspense sequence with the murderous babysitter, references Shivers: the apartment complex setting is strikingly similar to Starliner Towers, even down to the residents, including the geriatric couple who ride the elevators. By the same token, Blue Sunshine anticipates Romero’s Dawn of the Dead in striking ways: there is a gun store scene very similar to that of Dawn of the Dead, in which Zipkin arms himself in defence against Mulligan; and their final showdown takes place in a shopping mall, in which the bald-headed showroom dummies are easily mistaken for zombies (indeed Lieberman’s film ends with a zombie-Mulligan being gunned down in a shopping mall).

The key apocalyptic horror films of the 70s represent a sustained and developing enquiry into the breakdown of American society, locating its pathology in the very ‘frontier spirit’ that underlies the American Way. The interplay between genre and authorship can be seen in the remarkable intertextuality of these films: a direct result of the cultural interaction and exchange between horror directors in their richest period of achievement. Further example would be the continuity of theme in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Hills Have Eyes and Just Before Dawn. This can be partly attributed to the genre savvy of the film-makers but also to their continuing sense of shared enquiry into the dark heart of the American pioneer myth, with each film building upon theme successively. One gets the sense of a baton being passed back and forth within 1970s horror – from Romero (Night of the Living Dead) to Craven (Last House on the Left) to Hooper (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre) to Cronenberg (Shivers) to Lieberman (Blue Sunshine) and back to Romero (Dawn of the Dead) – a working through of the issues collectively - as each delves deeper into the nature of the ‘apocalypse’ facing the society of its time.

But whereas the early films of Hooper and Craven were unwilling to move beyond the apocalyptic, the work of Cronenberg, Lieberman and Romero in the 70s moved towards the possibility of a new order. Shivers offered a vision of sexual revolution based on the writings of Freudian psychologist, Norman O. Brown that was deeply ambivalent. In its portrayal of the 1970s as a consumerist dystopia whose revolutionary ideals have been replaced by mass psychosis (zombie-ism), Blue Sunshine bridges the ideological gap between Shivers and Dawn of the Dead. All three films critique the consumer-capitalist impasse of the 1970s but Blue Sunshine provides the crucial transition between the ambivalent sexual politics of Shivers and Dawn of the Dead’s tacit observation of alternative ideologies and countercultural values. In this respect Lieberman’s films - Blue Sunshine, especially - are important but often overlooked contributions to The American Nightmare cycle that began with Night of the Living Dead.

Blue Sunshine places itself, then, firmly alongside Shivers and Dawn of the Dead in the ‘invasion-metamorphosis’ sci-fi/horror subgenre as described by critic Andrew Tudor: “collectively, we have become potential victims, to be transformed into zombies, gibbering maniacs or diseased wrecks,” writes Tudor in Monsters and Mad Scientists: A Cultural History of the Horror Movie:

Lieberman had originally set the film in New York, with elaborate flashback sequences showing the characters’ college days; however, for budgetary reasons he ended up cutting those scenes and transposing the story to Los Angeles. In many ways that transposition helps the film. In Shivers and Rabid (1976) Cronenberg emphasises the brutalist architecture of Montreal as a dehumanising influence on the characters; in Blue Sunshine Lieberman uses the sterile modernity of Los Angeles, with its endless shopping centres and boutique malls, to similar effect, providing an ironic backdrop to the drug burn-out narrative. Indeed the intertexuality of the Cronenberg films and Blue Sunshine is underlined by the similarity of several key scenes in the work of both directors: in Blue Sunshine, Jerry anxiously watches his friend, Dr Blume - whom he thinks might be LSD-‘infected’ – perform surgery on a woman with cancer. The suspense is partly generated by Lieberman’s playing on the audience’s genre expectations: a similar scene appears in Rabid, in which a surgeon succumbs to the rabies virus while working on a patient and turns homicidal in the operating theatre.

Blue Sunshine’s central suspense sequence with the murderous babysitter, references Shivers: the apartment complex setting is strikingly similar to Starliner Towers, even down to the residents, including the geriatric couple who ride the elevators. By the same token, Blue Sunshine anticipates Romero’s Dawn of the Dead in striking ways: there is a gun store scene very similar to that of Dawn of the Dead, in which Zipkin arms himself in defence against Mulligan; and their final showdown takes place in a shopping mall, in which the bald-headed showroom dummies are easily mistaken for zombies (indeed Lieberman’s film ends with a zombie-Mulligan being gunned down in a shopping mall).

The key apocalyptic horror films of the 70s represent a sustained and developing enquiry into the breakdown of American society, locating its pathology in the very ‘frontier spirit’ that underlies the American Way. The interplay between genre and authorship can be seen in the remarkable intertextuality of these films: a direct result of the cultural interaction and exchange between horror directors in their richest period of achievement. Further example would be the continuity of theme in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Hills Have Eyes and Just Before Dawn. This can be partly attributed to the genre savvy of the film-makers but also to their continuing sense of shared enquiry into the dark heart of the American pioneer myth, with each film building upon theme successively. One gets the sense of a baton being passed back and forth within 1970s horror – from Romero (Night of the Living Dead) to Craven (Last House on the Left) to Hooper (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre) to Cronenberg (Shivers) to Lieberman (Blue Sunshine) and back to Romero (Dawn of the Dead) – a working through of the issues collectively - as each delves deeper into the nature of the ‘apocalypse’ facing the society of its time.

But whereas the early films of Hooper and Craven were unwilling to move beyond the apocalyptic, the work of Cronenberg, Lieberman and Romero in the 70s moved towards the possibility of a new order. Shivers offered a vision of sexual revolution based on the writings of Freudian psychologist, Norman O. Brown that was deeply ambivalent. In its portrayal of the 1970s as a consumerist dystopia whose revolutionary ideals have been replaced by mass psychosis (zombie-ism), Blue Sunshine bridges the ideological gap between Shivers and Dawn of the Dead. All three films critique the consumer-capitalist impasse of the 1970s but Blue Sunshine provides the crucial transition between the ambivalent sexual politics of Shivers and Dawn of the Dead’s tacit observation of alternative ideologies and countercultural values. In this respect Lieberman’s films - Blue Sunshine, especially - are important but often overlooked contributions to The American Nightmare cycle that began with Night of the Living Dead.

Blue Sunshine places itself, then, firmly alongside Shivers and Dawn of the Dead in the ‘invasion-metamorphosis’ sci-fi/horror subgenre as described by critic Andrew Tudor: “collectively, we have become potential victims, to be transformed into zombies, gibbering maniacs or diseased wrecks,” writes Tudor in Monsters and Mad Scientists: A Cultural History of the Horror Movie:

(y)et however vast its scale, the heart of this narrative lies in the emphatically internal quality of its threat. It is not simply that we may be destroyed, as we might have been by a score of traditional movie monsters. It is also that we will be fundamentally altered in the process; that our humanity itself is at risk. [13]

Intriguingly, the invasion-metamorphosis narrative that Tudor describes, perhaps because of its emphasis on human transformation as allegory of social and political change, seems to form the basis of the more optimistic horror films of the 1970s. Whereas the savagery/civilisation contradiction of Last House on the Left, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and The Hills Have Eyes (derived largely from the American revisionist western) seems impassable – it is presented as essentially two sides of the same coin – the living/dead dichotomy of Blue Sunshine and Dawn of the Dead is surpassable, although, admittedly, it requires a fundamental shift in the values of society – which the films suggest nothing short of a countercultural revolution can bring about.

Accordingly, Blue Sunshine’s protagonist, Jerry Zipkin, is defined as a counterculture figure, an ‘un-reconstituted hippie’. Early in the story, it is revealed that, in the words of the detective following the case, Jerry is “erratic as hell”. He graduated from Cornell but now, ten years later, “hasn’t got a pot to piss in”. He has gone through a number of jobs. “He quit his last one”, we are told, “because the firm wouldn’t hire enough women”. Zipkin, because of his integrity, his adherence to the progressive values of his youth, his refusal to sell out, has become labelled a social misfit. Hence, he is fingered as the immediate suspect in the murder investigation. Jerry seems immune to the psychosis spreading through the erstwhile peace and love generation (which is itself a metaphor for their selling out to materialistic values); although at times Lieberman asks us to question this immunity, as Jerry’s own behaviour becomes increasingly erratic (Lieberman attempts to play on our paranoia in a number of scenes, making us think that Jerry might be starting to suffer the effects of the drug, however Zalman King’s idiosyncratic performance makes this work less effectively than it might otherwise have).

Zipkin’s nemesis is Ed Flemming, the dealer turned politician. “We have lost a trust,” Flemming announces in his campaign speech, “a trust in ourselves, a trust in our fellow Americans and a trust in the leadership of our government”. Flemming is depicted as a hypocrite and self-serving parasite, part of the corruption that besmirched 60s counterculture. Fittingly, his election campaign rally is held at Shopper’s World, a large mall, which also houses a discotheque, thus closely aligning his values with those of consumerism. Disco, in Blue Sunshine, is seen as part of the ideological superstructure of 1970s consumerism, further evidence of the kind of commodified sexual freedom/ Marcusean repressive desublimation exemplified by the Starliner Towers complex in Cronenberg’s Shivers. Incidentally, Lieberman attributes Blue Sunshine’s popularity among the late 70s American punk music scene (where the film was regularly screened as background visuals in New York’s music clubs) to its discotheque sequences which, according to Lieberman, “shit over disco”. [14]

The conclusion of Blue Sunshine remains optimistic: ultimately, Zipkin (who has retained his basic integrity from his college days and not sold out like his contemporaries) prevails and he is vindicated. His defeat of Mulligan in the shopping mall is the triumph of integrity over corruption, of 1960s counterculture values prevailing in the age of consumerism; perhaps even the start of a backlash against the capitalist ‘reality’ of the 1970s in favour of a return to flower-power idealism. Lieberman invites us to consider these possibilities as the camera tracks away from Jerry and the unconscious Mulligan, to retreat through the aisle of consumer goods, past televisions blaring out Flemming’s campaign: “it’s time to make America good again!” We need more people like Zipkin, the film seems to be saying in its sardonic way, people who are immune to the lure of consumerism. Lieberman cannot resist a final irony, however, informing us in a title card that “two hundred and fifty-five doses of ‘Blue Sunshine’ still remain unaccounted for”. The immediate threat may have been fended off, but the wider crisis remains.

The On-Going Auteur: Jeff Lieberman at Cine Excess VIII

Lieberman’s appearance as Guest of Honour at 2014’s Cine Excess VIII speaks to the continuous market value of his films, and his lasting presence as a cult filmmaker. His reputation has continued to grow in recent years as a result of his active on-line presence; his use of social media and dedicated website to maintain contact with fans; an increasing awareness of his work on fan sites and cult movie forums; regular repertory screenings of his films; and the steady reissue since 2002 of Lieberman’s back catalogue on DVD, Blu-ray and streaming media, as well as the release, in 2003, of his most recent film, Satan’s Little Helper.

In conversation, and during his participation in the industry panel on crowdfunding and the horror film, Lieberman reflected on being a cult director in the digital age. He has responded to horror fandom in a number of interesting ways.

Demand for his work led him to set up a distribution website for Remote Control, so that the film can be sent direct to fans on limited edition DVD and Blu-ray. Although Remote Control receives TV airings outside the US by Studio Canal, in the United States and the UK it had remained unseen since its VHS release in 1988. The domestic rights were owned by Carolco whose bankruptcy had tied up the film (and other titles) since 1995. Eventually Lieberman received the green light from former Carolco executive Andrew Vajna to release the film himself after spending a year trying to buy back the rights. He personally oversaw the 2K HD transfer from a good quality print that he found in Paris and had shipped over to the States. More recently, the discovery of the lost negative to Blue Sunshine in 2015 has enabled Lieberman to similarly re-master that title in 4K for screenings at cinemas committed to cult programming, such as the Silent Movie Theater in Los Angeles and the Alamo Drafthouse Yonkers, and for eventual Blu-ray release and streaming in America. Lieberman thus remains very much a part of the cult film community through events such as Cine Excess, regularly attending screenings of his films and making them available to new audiences in upgraded digital formats.

A number of films by Lieberman’s horror contemporaries have, of course, been remade (eg. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre [2003], Dawn of the Dead [2004]), The Hills Have Eyes [2006]), and the reactions of critics and fans to these remakes have been generally negative. Nevertheless, Lieberman remains open to his own films being ‘reimagined’. When asked about the proposed remake of Squirm, Lieberman expressed enthusiasm for the possibilities of CGI in delivering what he believes could be an improved version of the original. Although venerated by fans for its special make up effects by Rick Baker, Lieberman regards the shortcomings of Squirm in terms of its budgetary limitations: “to get that one worm going up the side of the face was such a big deal and a budget breaker. It took half a day to achieve that one make-up effect”. [15] Lieberman necessarily scaled back the effects sequences of Squirm in order to meet the tight budget. CGI would enable him to achieve a film that he feels would therefore be closer to his original scripted vision, giving the film more of the ‘yukkie-stuff’ (the film’s title, of course, signals the film’s intended bodily affect). Similarly, Lieberman contends that the mooted remake of Blue Sunshine (currently in development with Vincent Newman as producer and Peter Webber directing), in terms of its theme of “decisions we made in our youth coming back to haunt us in horrific ways as adults”, would “resonate well with Millennials”. [16] In this way Lieberman challenges those fans and critics predisposed against the remaking of sacred horror film texts; while there is a tendency for cult movie fans to canonise directors for their past achievements, it is important to acknowledge Lieberman’s authorship in terms of a career and ‘oeuvre’ that is on-going and evolving.

On the subject of crowdfunding for feature films, Lieberman has mixed feelings. He admits that it is difficult for independent filmmakers to secure funding, and remains open to the possibilities for a production on a low budget (Satan’s Little Helper was shot on HD with a small cast and crew). Generally, however, he disagrees with the sense of entitlement that crowdfunding can embody for first time filmmakers: “You’re basically asking the public for money just because you want to make a film.” [17] Gatekeepers may be a necessary evil, ensuring a certain level of quality. Making reference to Squirm, he comments: “I wrote a script that was good enough for two producers to want to make.” Having said this, Lieberman admits that his own cult status means that crowdfunding may become a viable option for him if a project is “inherently cheap so that it can be made on a low budget”. The prospect, for cult film fans, is certainly intriguing. As Lieberman quipped during the panel discussion, “If the fans really want it that badly, and they’re willing to put money into it, who am I to blow against the wind.”

A number of films by Lieberman’s horror contemporaries have, of course, been remade (eg. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre [2003], Dawn of the Dead [2004]), The Hills Have Eyes [2006]), and the reactions of critics and fans to these remakes have been generally negative. Nevertheless, Lieberman remains open to his own films being ‘reimagined’. When asked about the proposed remake of Squirm, Lieberman expressed enthusiasm for the possibilities of CGI in delivering what he believes could be an improved version of the original. Although venerated by fans for its special make up effects by Rick Baker, Lieberman regards the shortcomings of Squirm in terms of its budgetary limitations: “to get that one worm going up the side of the face was such a big deal and a budget breaker. It took half a day to achieve that one make-up effect”. [15] Lieberman necessarily scaled back the effects sequences of Squirm in order to meet the tight budget. CGI would enable him to achieve a film that he feels would therefore be closer to his original scripted vision, giving the film more of the ‘yukkie-stuff’ (the film’s title, of course, signals the film’s intended bodily affect). Similarly, Lieberman contends that the mooted remake of Blue Sunshine (currently in development with Vincent Newman as producer and Peter Webber directing), in terms of its theme of “decisions we made in our youth coming back to haunt us in horrific ways as adults”, would “resonate well with Millennials”. [16] In this way Lieberman challenges those fans and critics predisposed against the remaking of sacred horror film texts; while there is a tendency for cult movie fans to canonise directors for their past achievements, it is important to acknowledge Lieberman’s authorship in terms of a career and ‘oeuvre’ that is on-going and evolving.

On the subject of crowdfunding for feature films, Lieberman has mixed feelings. He admits that it is difficult for independent filmmakers to secure funding, and remains open to the possibilities for a production on a low budget (Satan’s Little Helper was shot on HD with a small cast and crew). Generally, however, he disagrees with the sense of entitlement that crowdfunding can embody for first time filmmakers: “You’re basically asking the public for money just because you want to make a film.” [17] Gatekeepers may be a necessary evil, ensuring a certain level of quality. Making reference to Squirm, he comments: “I wrote a script that was good enough for two producers to want to make.” Having said this, Lieberman admits that his own cult status means that crowdfunding may become a viable option for him if a project is “inherently cheap so that it can be made on a low budget”. The prospect, for cult film fans, is certainly intriguing. As Lieberman quipped during the panel discussion, “If the fans really want it that badly, and they’re willing to put money into it, who am I to blow against the wind.”

Footnotes

- Alexander, C. ‘Interview: Director Jeff Lieberman Talks BLUE SUNSHINE 4K Restoration’. Shock Till You Drop. https://www.shocktillyoudrop.com/news/features/389261-interview-director-jeff-lieberman-talks-blue-sunshine-4k-restoration/

- Derry, C. (2009) Dark Dreams 2.0: A Psychological History of the Modern Horror Film from the 1950s to the 21st Century. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 55-87

- Andrews, S. Rue Morgue Podcast, June 22, 2011. https://www.rue-morgue.com/2011/06/rue-morgue-podcast-jeff-lieberman

- Quoted in Crawley, T. (1977) ‘Blue Sunshine’, House of Hammer, 2, (3), 16.

- Wood, R. (2003) Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan…And Beyond. New York: Columbia University Press, 63-84.

- Rue Morgue Podcast

- Rue Morgue Podcast

- Collins, F. ‘Squirm’. Cathode Ray Tube. https://www.cathoderaytube.co.uk/2013/09/squirm-dual-dvd-and-blu-ray-edition.html

- See Towlson, J. (2014) Subversive Horror Cinema: Countercultural Messages of Films from Frankenstein to the Present. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland & Co, 1.

- Rose, J. (2009) Beyond Hammer: British Horror Cinema Since 1970. Leighton Buzzard: Auteur Publishing, 137-139.

- Rose 2009, 138

- Rose 2009, 139

- Tudor, A. (1989) Monsters and Mad Scientists: A Cultural History of the Horror Film. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 97.

- Harding, B. ‘The Monsters Chat with Jeff Lieberman.’

https://www.monstersatplay.com/features/interviews/jeff-chat.php - Squirm Q&A, November 14, 2014. Cine Excess VIII: ‘Are you Ready for the Country: Cult Cinema and Rural Excess’.

- McNary, D. Horror Film. ‘‘Blue Sunshine’ Gets Remake From ‘We’re the Millers’ Producer’. Variety, October 24, 2014. https://variety.com/2014/film/news/blue-sunshine-remake-vincent-newman-1201338371/#

- ‘Cult Crowdfunders: New Audiences, New Funders and the Cult Indie Scene’, Q&A, November 14, 2014. Cine Excess VIII: ‘Are you Ready for the Country: Cult Cinema and Rural Excess’.